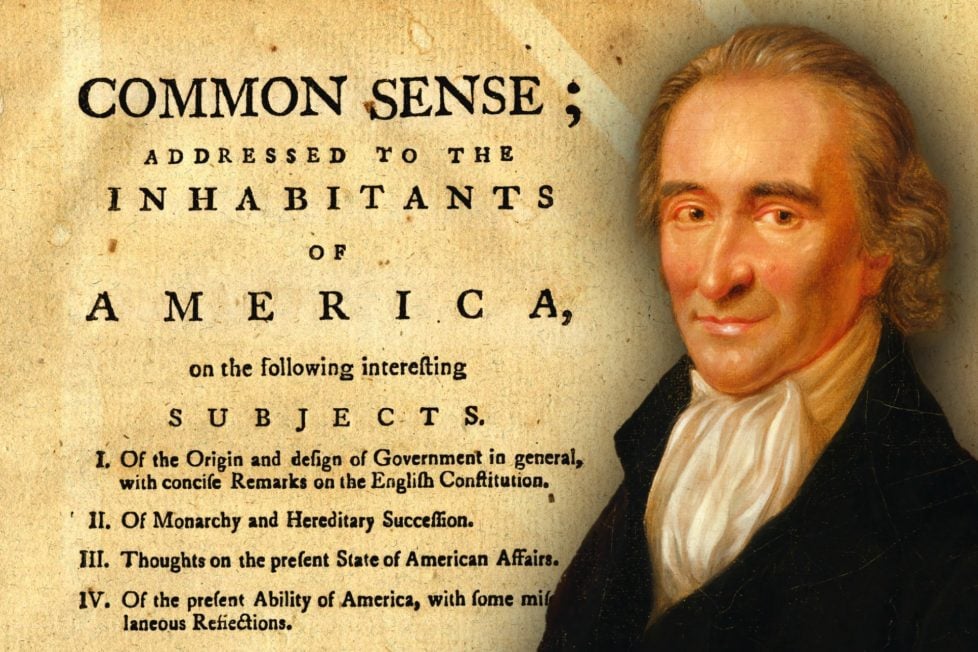

Thomas Paine and Common Sense

The lasting effect of a few pages on the course of history.

Table of Contents

ToggleOn January 29, 1737, Thomas Paine was born in Thetford, England into a family which included a Quaker father and an Anglican mother. His family was responsible for teaching him the craft of stay making, which was the fashioning of corsets for women. While he practiced the trade occasionally throughout his life, he harbored dreams of adventure and experience and twice ran away from home in order to enlist on ships and go to sea. The following decade of his life is shrouded in some mystery, but it is known that he married a woman named Mary Lambert in 1759, who died in childbirth after only a year.

Following his wife’s death, he became involved in the excise service in and around London. He was released from service likely due to fraudulent “stamping” of goods. Subsequently, Paine plied a myriad of trades which included teaching, working as a tobacco dealer, and there are rumors of Paine working as a preacher, among other things.

Paine remarried in 1771, but the marriage soon failed. He was removed from the excise service for the second time after petitioning for reentry. Paine sold his business and belongings and was awarded a settlement from his wife after divorce. Fortunately, he met the famous American philosopher and inventor, Benjamin Franklin. Franklin suggested that Paine move to the American colonies and even provided him with letters of introduction to help him get started across the ocean.

In November of 1774 he arrived into a wildly chaotic and uncertain situation in the colonies. The upstart Americans were upset about a ruling power thousands of miles across an ocean levying excessive taxes without having any say in the process themselves. Incidentally, Mr. Paine had written material critical of the English government while an employee in the excise office, wherein he claimed that a raise in pay would have been very effective at helping end corruption in government, an essay for which he was excused from the service for the second time.

April 19, 1775, was a pivotal day in American history. In an attempt to confiscate the munitions that colonists were stockpiling, the British met with real colonial resistance for the first time at the Battles of Lexington and Concord. After the battles, Paine began arguing that the Americans should aim for a complete break from the British Crown, rather than a simple end to “taxation without representation.” In order to further the cause of separation he penned one of the most famous and influential pamphlets in American history, entitled Common Sense. The pamphlet would influence many of the men in the Continental Congress and was read by hundreds of thousands of average citizens in every colony. It is widely believed that Common Sense led directly to the Declaration of Independence, and the seemingly hopeless attempt at defeating the British in open conflict.

At 47 pages, Common Sense was published on January 10, 1776. The American populace at that time numbered around 2-3 million. And after the original printing, 25 editions were necessary to meet the insatiable demand, and it became the best-selling pamphlet in American history and is still widely available today, nearly 250 years later.

The pamphlet consists of a preamble and 4 main sections. The introduction speaks of the motivation behind the masterpiece and describes its content. Paine explains that the ideas in Common Sense may not yet be fashionable to procure them “general favor” in the eyes of the colonists, as for the most part, they were not ready to split from England. However, Paine’s iconic writing would change the minds of a large percentage of the previously reticent Americans.

Decreeing that “the cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind” Paine describes the oppression of the British Crown and “their” Parliament as detrimental to the colonies and leaves little doubt about the direction in which the subsequent pages would take. While Paine uses the emotion and unrest of the colonists in a clear manner, he also attempts to distance himself from any outside political influence. He states, “that he is unconnected with any party, and under no sort of influence, public or private, but the influence of reason and principle.”

Paine describes the unfortunate necessity of government and the evils that can very swiftly arise from an oppressive form of said government. He claims that, “society in every state is a blessing, but Government, even in its best state, is but a necessary evil; in its worst state an intolerable one.” Paine provides many unforgettable quotes throughout the entirety of the piece, many of which have become American Scripture and are quoted by freedom loving people throughout the world, not only in America.

Common Sense lays out a list of condemnations of the long-standing forms of monarchical government. After describing the fallacies of monarchy and hereditary title he concludes that “there is something exceedingly ridiculous in the composition of monarchy” and states the “whole character to be absurd and useless.”

Paine moves on to discuss what is entitled “Thoughts on the Present State of American Affairs.” This section is self-explanatory and attempts to present the reader with “simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense.” He attempts to convince the reader of the righteousness of the cause of separation and correctly surmises that those opposed to the American separation “will be remembered by future generations with detestation,” and that “the sun never shined on a cause of greater worth.” Surely, words like these coming from such a recently arrived English immigrant must have been surprising to many readers, and likely lent weight to the speaker in the eyes of the colonists Paine goes on to describe what he believes to be a prudent organization of government and a few ideas on how to move forward as an independent nation.

The remainder of the pamphlet discusses what Paine believes to be the available abilities of the Americans to defeat the British in open conflict. While enumerating much of what the colonists have on hand in order to fight the British, Paine concedes that “tis not in numbers but in unity that our great strength lies.” However, the author believed that the colonies were capable of repelling “all the force of the world” even at that time, an unlikely prospect to be sure.

One of the most prominent and outspoken leaders of the move toward separation was John Adams. David McCullough’s biography of Adams briefly explains that Adams bought two copies of the pamphlet in New York, and sent one on to his enormously influential wife, while keeping and reading the other. Initially, according to McCullough, Adams really enjoyed the pamphlet. However, after multiple readings, and much reflection, Adams began to believe that Paine seemed to be “a better hand at pulling down than building.” Adams had seemingly already shifted to “an intention to turn to building again.” While the building of a government seems to be a more benevolent aim than tearing one down, doing so would not have been possible without first destroying the old ways of tyranny and monarchy, and Paine most assuredly aided in the first necessary step.

Whether Adams really believed that Paine was intent on tearing things down, or his well-known vanity forced him into a contrary stance when confronted with a previously unknown Englishman stealing his thunder, we shall never know. Regardless there can be little doubt as to the impact that Paine had on some of the less self-absorbed founders and philosophers of the day.

Benjamin Franklin, whose role in the founding of the new country cannot be denied, was a friend and mentor to Paine. And it is widely believed that Franklin played a significant role in the writing of Common Sense. However, when reading the writings of Dr. Benjamin Rush on the subject, he states that Franklin made no addition to the manuscript when Paine asked him to review it, “but a passage was struck out, or omitted in printing it.” Nevertheless, Franklin was clearly a major influence on the life and beliefs that Paine held and presented to the American people of the day.

Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, was undoubtedly influenced by Paine. The similarities between the two documents is clearly apparent. When reading Common Sense and the accusations against monarchy, the similarities with the Declaration are obvious. While the two men were of very incredibly different backgrounds, they seem to have developed very similar ideals about American separation and independence.

Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence led the colonies to finally declare the separation outright, and in October of 1781, Lord Cornwallis surrendered his forces to Washington, effectively ending the Revolutionary War. Paine’s pamphlet is often viewed as the original declaration of freedom from the British.

The impact on world history since the separation is undeniable. The United States is often demonized in modern culture as an imperialist or oppressive power. While mistakes have been made, the overall influence that the United States has had on the world stage has been positive. From the introduction of a multitude of technological advancements to the assistance that has been rendered to Europe during the Second World War, the American experiment has been incredibly important, and for most, positive.

Thomas Paine introduced an ideal in 47 pages that changed the course of human history. Without Common Sense, it is unlikely that the American Revolution would have taken place, and certain that it would have been different had it not been read by so many. Paine has no statues in Washington D.C., and only a small percentage of modern Americans have ever read his work or know his name, but his contribution to the creation of a new and independent world power is undeniable.