Snake Handling Churches in America

Examining the unusual tradition of serpent handling within American religious practices.

Examining the unusual tradition of serpent handling within American religious practices.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe United States is an unusual place, to say the least. The number of subcultures within America is mind-boggling: “tree-huggers,” militias, low-riders, cowboys, nerds, fitness junkies, and thousands of others, sometimes all seeming to compete with each other for the title of “Most Unusual.”

But perhaps the most unusual of all the distinct groups in the USA are the snake-handlers. No, not the kind you see in zoos – the kind you see in churches. That’s right. Churches. Though their numbers aren’t what they used to be, there are still over 125 known snake-handling congregations in the United States and possibly dozens more in the hills, mountains, and hollers of Appalachia.

As you may know, many conservative denominations take the Bible as “the literal Word of God.” There’s nothing unusual about that within Christianity or any other of the world’s major religions, but the interesting thing about the Pentecostal churches in Appalachia that practice snake-handling is their focus on one particular section of the Book of Mark. Mark 16 verse 18 states:

“They shall take up serpents; and if they shall drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them: they shall lay their hands upon the sick, and they shall recover.”

Believers will also mention Luke 10:19:

“Behold, I have given you power to tread upon serpents and scorpions, and upon all the power of the enemy: and nothing shall hurt you.”

and Acts 28:1-6 in which the Apostle Paul is recorded as handling a deadly serpent without harm.

The handling of deadly snakes and, sometimes, the drinking of the poison strychnine are all part of a peculiarly American form of worship, which enjoyed a heyday in the 1940s and 1950s, though its roots in America may go back to colonial times.

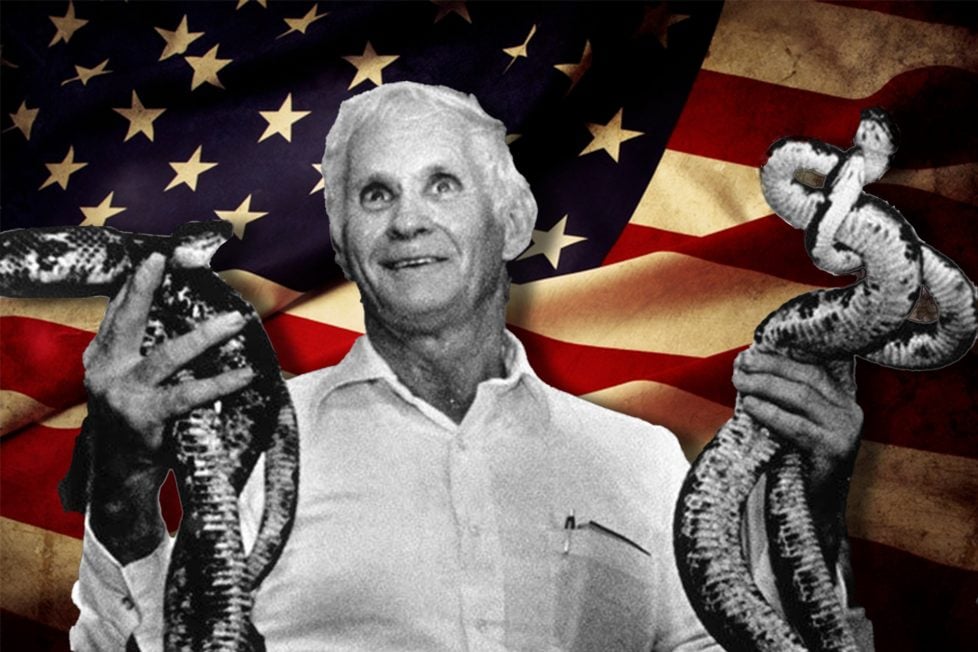

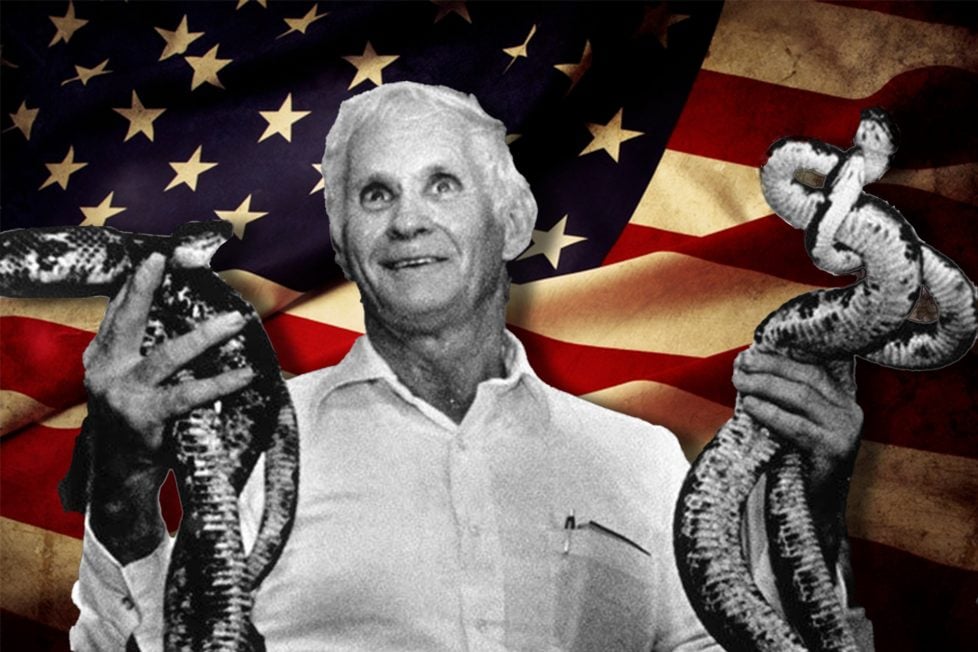

Around 1909, George Hensley, a heavy drinker struggling with his own alcoholic demons, was walking in the woods of eastern Tennessee when he saw one of the many poisonous snakes of the area at his feet. Without thinking, Hensley picked up the serpent, stroked it, held it for a few minutes, and then let it go – without harm. He became convinced that God had protected him because he had been asking for divine help with his many personal issues.

It’s said that Hensley brought a snake to a church service in 1909, and by 1914, apparently never having been harmed by handling the snakes, he got tacit permission from the Pentecostal Church of God to incorporate snake handling in his preaching as a testament to his faith.

Appalachia has always been poor, and the Great Depression that began in 1929 in the rest of the country hit Appalachia early and hard, as it did with many rural communities. By the time of the Wall Street Crash, many people in Appalachia and neighboring areas had latched onto charismatic preachers who traveled from place to place, holding “revival meetings” that took place almost every day of the week. Snake handling became exceptionally popular among Pentecostals and the predominant Christian sect in the region, the Baptists. People were entranced and amazed by men and women dancing along with choir and band music while “speaking in tongues” or preaching while handling the rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths of the region, all of which can deliver a painful and frequently fatal bite.

At its height, snake-handling churches saw thousands of people coming to their services and large outdoor revival meetings. However, mainstream Pentecostal and Baptist churches began discouraging the practice when the Depression started.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that people in the Appalachians take the US Constitution very seriously, especially the First Amendment, which states in part: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof;…” If the US government could not stop snake-handling (at least at the time), then the mainstream congregations of the region surely couldn’t either, so Hensley and others since began their own churches. Hensley’s church was called the “Church of God with Signs Following.”

The height of Hensley’s popularity came in the late 1940s, and he traveled through Appalachia and sometimes into the Deep South, preaching and handling snakes. His charisma and the fact that he had been handling snakes with no apparent ill-effect made people overlook his many faults, which included alcoholism, domestic abuse, being married three times, and having thirteen children.

Towards the end of his life, Hensley claimed to have been bitten over 400 times – with little or no effect. However, on July 24th, 1955, he was bitten while preaching in Florida, perhaps by the deadliest venomous snake in North America, the ordinarily placid coral snake. He became violently ill, refused medical care, and died the next day.

The snake-handling congregations believe that if you’re “right with God,” whether living a godly life or directly communicating with the divine, you won’t be harmed by a snake, even if you are bitten. And should you get sick or lose a finger, hand, toe, or foot due to the necrosis caused by snake venom, then that is “the will of God.” Likewise, should a person die – then fatalistic believers will often say, “It was their time.” Many, but not all, snake-handling preachers refuse medical treatment when bitten. Some snake handlers have said they were bitten after picking up a serpent when they knew that things “weren’t right” – ignoring a message from God.

But it’s not just the preachers that handle snakes. Congregants moved to do so will come forward and be given a snake or two, or even three or more, to grasp in their hands, wrap around their necks, and rub against their faces, often gyrating wildly or hopping while “speaking in tongues.” Children are not allowed to handle snakes, but they are often present in the small cabin-style churches where the services take place – services that can last for hours. At times, preachers will sip diluted strychnine from a Bell jar set on their podium, and both men and women will come forward to hold fire from kerosene-soaked tapers in bottles to their flesh in a symbolic recreation of the fire seen above the heads of the Apostles on the day of Pentecost in the Book of Acts.

People “called” to snake handling claim that while handling serpents, they feel as if “the entire world disappears” and that they are one with the Holy Spirit. Neuro-biologists say this feeling is the intense focus, fear, and massive amounts of adrenaline pulsing through the body.

Besides a religious revival and the Great Depression, the 1920s also saw the development and popularity of “moving pictures” and newsreels. In addition to seeing important events as they happened, newsreels brought unique, unusual, and hard-to-believe subjects to communities throughout the country. As you can imagine, many newsreels from the 1920s to the early 1950s showed snake-handling churches. While people across the country were fascinated, many fundamentalist religious leaders realized that people were equating their churches and congregations with a practice that, despite its growing popularity and unusual nature, was still a minority practice – but a minority practice that might be keeping people from looking into their more mainstream congregations.

Then there were the deaths. Like Hensley in 1955, hundreds of people died from snakebite in plain view of others – including children, sometimes their own. In the 1930s, US states began restricting or banning the practice altogether. Today, only one state in the Union allows snake-handling churches to practice freely – West Virginia. Kentucky requires a unique and hard-to-get permit. In all other states, the practice is illegal but goes on secretly.

In West Virginia, snake-handling congregations and preachers, aided by the American Civil Liberties Union (“ACLU”), went to the state Supreme Court and won the right to continue the practice, arguing that snake-handling was an integral part of their belief and that its prohibition would be a violation of their First Amendment rights. That being the case, most snake-handling churches in the USA today are in the state. However, there are several known congregations in eastern Tennessee, northwest Georgia, and northern Alabama, though these are highly secretive and wary of strangers, for they are often ridiculed, and can be arrested or heavily fined.

Other states have dodged First Amendment issues regarding the churches and made snake handling an animal-rights issue. Aside from the stress, injuries, and death the snakes sometimes suffer while being used and swung about in services, many legal snake-handling churches have been accused of neglect. Some outsiders believe that poor feeding and neglect lead to snakes’ venom being less lethal, but that has not stopped people from dying because of, or as they might say, for their beliefs.

In 2013-14, the National Geographic Channel and VICE News did documentaries on the lives, careers, and deaths of snake-handling preachers in West Virginia. The most notable preacher was Jamie Coots, a giant of a man bitten at least eight times during his eighteen years of preaching with snakes, including losing his middle finger to necrosis after a rattlesnake bite. In February 2014, Jamie Coots was bitten again by a rattlesnake. He refused medical attention and died at home the next day in agony. One of his sons, Cody, has taken over the Full Gospel Tabernacle in Jesus’ Name Church in Middleboro, Kentucky, started by his snake-handling grandfather, Tommy. Like his father, Jamie was bitten while documentary cameras were rolling – in the temporal artery. Unlike his father, he accepted medical care, and though it was “touch and go” for a few days, Cody survived. After a long recovery, he returned to preaching according to the Gospel of Mark chapter 16, verse 18.