7 of the Most Intriguing Revenge Stories from History

Discover history's most gripping tales of poetic justice served.

Discover history's most gripping tales of poetic justice served.

Table of Contents

ToggleThere’s nothing more satisfying than a good revenge story, one that gets the blood pumping and the righteous anger flowing. Humans are vitriolic, savage beasts at times, and the story of one who rights those wrongs can go a long way to purging that sense of injustice. Not that there isn’t always a cost to revenge.

Here are seven of the most interesting revenge stories from history.

A ronin was a masterless samurai, and the tale of the 47 has given the ronin lasting fame.

Asano Naganori was a lord in Japan during the Edo period. In 1701, he was invited to help organize a reception at the behest of the emperor at the shogun’s court in Edo, now known as Tokyo. During this event, an official by the name of Kira Yoshinaka treated him poorly, insulting him at every opportunity.

Driven to rage, Asano drew his dagger and injured Kira before he was contained by the guards.

The shogun sentenced him to commit seppuku, a ceremonial form of suicide, as punishment for his crime. Asano left behind 47 of his samurai, now ronin.

The shogun forbade the samurai from exercising their right to revenge as defined by the warrior’s code, and Kira, afraid of retribution, surrounded himself with guards for two years following Asano’s death; however, the ronin, lulled Kira into a false sense of security by doing absolutely nothing.

Two years later, in January 1703, 46 of the ronin invaded Kira’s house, taking out several of his samurai and decapitating Kira as he hid. They placed his head on Asano’s grave.

Despite acting according to the warrior’s code, they had deliberately disobeyed the shogun, so they had known they would die. However, they were permitted to commit seppuku instead of being executed as criminals.

The Japanese commemorate these ronin annually on December 14.

Simon Wiesenthal and Serge and Beate Klarsfeld came from different countries and experienced World War II differently, but each was relentless in bringing Nazi war criminals to justice.

Wiesenthal, a Jewish Austrian Holocaust survivor, worked for the War Crimes Section of the US Army and pressured Western governments into the pursuit and prosecution of escaped Nazis.

Among those he helped capture were Adolf Eichmann, administrator of the Final Solution, Karl Silberbauer, Anne Frank’s captor, and Franz Stangl, commandant of the Sobibor and Treblinka killing centers.

Serge and Beate Klarsfeld, on the other hand, were a husband-and-wife Nazi-hunting team.

Serge witnessed his Romanian Jewish father being dragged off to Auschwitz at the age of 8 and never saw him again. In contrast, Beate is German, and for her, the hunt was an act of atonement for the sins of her country.

The pair were responsible for capturing Klaus Barbie, the Butcher of Lyon, and Maurice Papon, the police chief who introduced laws that led to the deportation of 140,000 French Jews.

They even attempted to shove Kurt Lishka, former head of the Gestapo, into the trunk of a car to drive him to France to stand trial, but they were caught by the police.

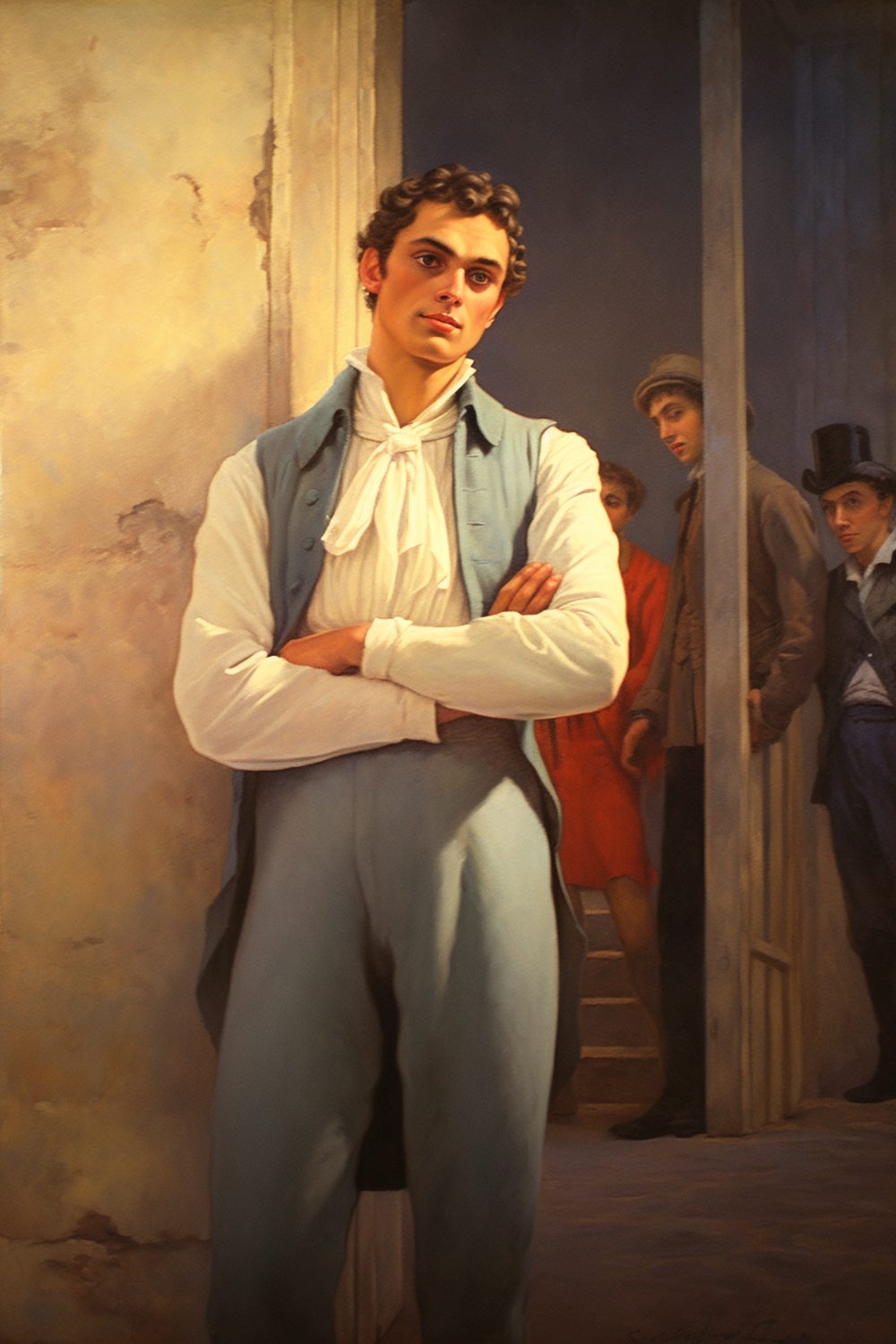

The revenge story inspired Alexandre Dumas to write the novel The Count of Monte Cristo, Picaud was wrongfully imprisoned, escaped, and found treasure, then let his elaborate revenge plan unfold over the course of years.

A shoemaker, Picaud got engaged to a wealthy woman in 1807. Three of his friends – Loupian, Chaubart, and Solari – became jealous of this turn of events and declared to the authorities that he was a spy for England. Picaud was subsequently imprisoned.

While in prison, Picaud dug a hole into the next cell and befriended a priest, who told him about some treasure hidden in Milan.

In 1814, the Imperial government fell and he was released. He immediately retrieved the treasure, returned to France, and spent ten years plotting how he was going to exact revenge.

Chaubart was murdered, Solari was poisoned, but Loupian, who had married Picaud’s ex-fiance, suffered the worst fate.

Picaud tricked Loupian’s daughter into marrying a criminal, burned Loupian’s restaurant down, and framed his son for stealing jewelry. The daughter died of shock, Loupian became poor, and the son was imprisoned.

Finally, Picaud confronted Loupian, now poor and broken, and stabbed him to death.

Frank witnessed his father’s murder in 1868 by a gang called The Regulators at the age of 8. His father’s friend, Mose Beaman, vowed that Frank would be cursed if he didn’t try to avenge his father’s death, and he then gave him his first gun.

So Frank learned how to shoot, becoming such a good shot he could take the head off a rattlesnake with either hand shooting from the hip.

When he outshot all the soldiers at Fort Gibson he was given the nickname ‘Pistol Pete’ by the commander.

For several years, Frank systematically tracked down the six men who had been responsible for his father’s death. By 1887, he had successfully managed to hunt down each of his father’s killers and shoot them dead.

Finally able to move on, he purchased some land in 1889 and got married in 1890.

La Maupin was anything but a conventional woman for the 17th Century. An excellent fencer and swordswoman, she wore men’s clothes, kissed women in public, and regularly dueled other men.

She was also an exceptionally talented singer, and when she was singing with the Marseille Opéra, she fell in love with a young woman, the daughter of a merchant.

Her parents, distraught at this turn of events, sent their daughter to a convent; however, La Maupin dressed as a postulant and entered the same convent, biding her time.

When an elderly nun died, she stole the nun’s body, placed it in her lover’s cell, and then promptly set it on fire. The young lovers then eloped together, fleeing the sentence of death that was placed on their heads in absentia.

A skilled gunfighter, copper miner, stagecoach driver, shotgun rider, saloon owner, and more, Wyatt Earp lived countless lives in his 80-odd years on this earth and died a legend.

However, he is most known for his gunfight at the OK Corral and his subsequent revenge mission.

Earp and his brothers, Virgil and Morgan, came into conflict with the Clanton gang, a bunch of outlaws causing trouble in the area, as they disrupted the Clantons’ cattle-rustling business while in Tombstone, Arizona.

Things came to a head on October 26, 1881, when the Clanton brothers met the Earps as they walked through an alleyway near the OK Corral. The Clantons opened fire, injuring Virgil and Morgan, although three of the Clantons were shot dead by Wyatt.

On March 18, 1882, the Clantons shot Morgan in the back as he played pool, killing him. Thus Wyatt began his long journey to revenge. After jumping off a train and gunning down one of the gang, Wyatt, his friend Doc Holliday, and several others rode out to eliminate all the men who had killed his brother.

In just over a year, the Earp posse had killed 19 men held responsible for his brother’s death. Only one escaped, turning himself over to the authorities instead of facing Wyatt.

The story goes that 25-year-old Julius Caesar was en route to Rhodes in 75 BCE when he was captured by pirates.

According to stories at the time, he read his poetry to the pirates and berated them for their lack of understanding, joined in their games but bossed them around like he was their commander, negotiated a higher, not lower, ransom for himself, and remarked often that he would crucify them when he was released.

They thought he was joking.

When the money came in after 38 days, he was released; but instead of relaxing, he raised a naval fleet in Miletus and set out to capture the pirates.

He found them on the island where they had camped before, and when he took them back, he kept his promise and had them all crucified.

All these stories speak of people who let nothing stand in their way, least of all time, to get their revenge. It stands to reason that you should be careful who you cross: those hellbent on revenge will let nothing stand in their way, not even the possibility of death.