Operation Fortitude: The Deception That Saved D-Day

On the eve of the Normandy landings, the Allies executed a brilliant deception, the most successful in history.

On the eve of the Normandy landings, the Allies executed a brilliant deception, the most successful in history.

Table of Contents

ToggleWinston Churchill once said that “In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.” In late 1940, even with the British Army barely recovered from the decisive defeat inflicted upon it during the fall of France and its evacuation from Dunkirk, British military thinking was turning to the prospects of a return to the continent.

This took longer than they might have thought – campaigns in North Africa and the Mediterranean consumed much time and energy. Landing craft design and production took a while to get underway. But, by early 1943, the British and Americans had agreed that an amphibious armed assault on France would take place somewhere in the middle of 1944. It would become known as Operation Overlord. By the end of 1943, the Allies had gained some invaluable experience of amphibious invasions – Dieppe, US landings in Morocco and Algeria, Sicily and Italy.

But where and when? The Germans commanded the entire Western European coastline, from the northern tip of Norway in the Arctic Circle, down to the Pyrenees and the frontier with neutral Spain.

Realistically, there was only a limited range of landing options for a quarter of a million soldiers. The disaster at Dieppe in 1942 had shown that attempting to attack a defended city could end horrifically. This pointed to the need for long, flat, firm beaches. Norway and the west coast of France might have been suitable for brief commando raids, but any area that put an invasion force beyond the range of powerful fighter air cover made attack highly risky.

In the end, for the invasion planners, it boiled down to two plausible options that offered suitable landing beaches and were close enough for reliable air protection – a direct and short assault across the channel from Dover (you can literally see France from Dover) or a longer move south, to the extensive holiday beaches of Normandy. As the original planning architect of Overlord, General Fredrick Morgan put it in his memoirs, it was “…either the Pas de Calais coast about Boulogne, Calais and Dunkirk or the Norman beaches about Bayeux and Caen.” The Germans had better fortifications and troops in the Calais area. Normandy was the preferred option.

As 1944 dawned, Allied planning was at full speed – considerations of weather, tides, moon and production of the critical landing craft meant the initial invasion date could be May at the earliest. This later slipped to early June. Delays into July or later could not be countenanced. In fact, it is no exaggeration to say that the invasion could not afford to fail.

Several hundred thousand soldiers and tens of thousands of tanks, aircraft and other pieces of equipment were being readied for what would become the largest amphibious assault in history.

An amphibious assault is one of the most risky and potentially bloody of all military manoeuvres. The biggest headache for the planners, generals and political leadership, amidst all this intense activity, planning and preparation – much of which was highly public and visible – was the fear that the Germans would find out the time and place of the landing and thus be prepared and ready.

The mission, therefore, was to keep the Germans guessing as to the location and timing of the landings. There were two overlapping concepts at work – one was to conceal the location of the landings, the other was to slow the arrival of German reinforcements from other fronts by creating the impression of additional threats elsewhere. A complex series of deception operations were devised, intended to confuse, distract and complicate German decision making and reactions. They were under the overall codename of Bodyguard.

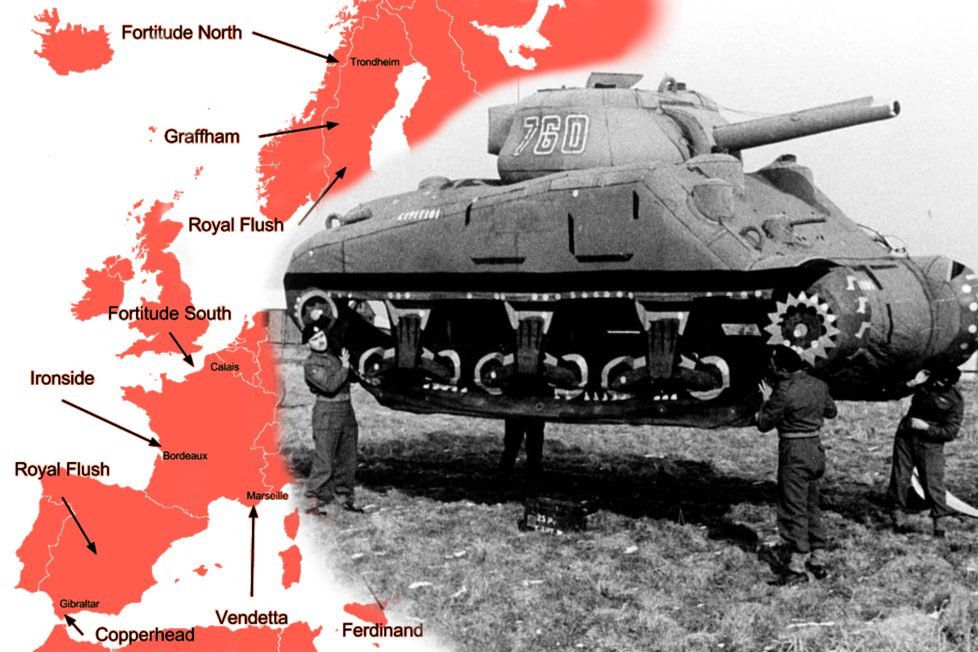

What we are interested in here is the operation in relation to the Normandy landings. This was Operation Fortitude. Fortitude itself was divided into two parts – Fortitude North and Fortitude South. Both involved the creation of fake armies that would lead German intelligence to the wrong conclusions about the invasion of Europe.

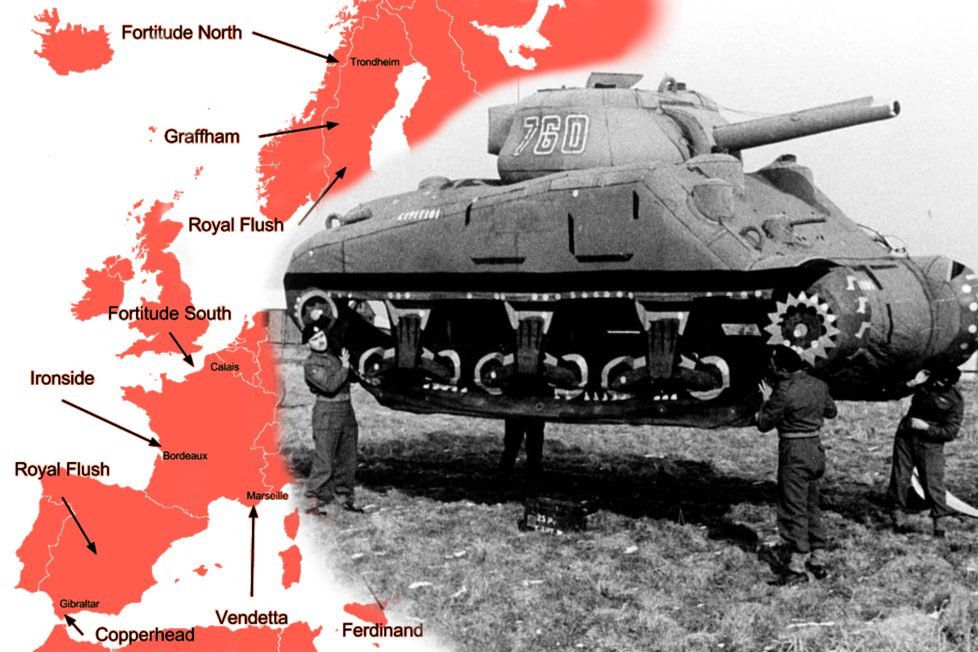

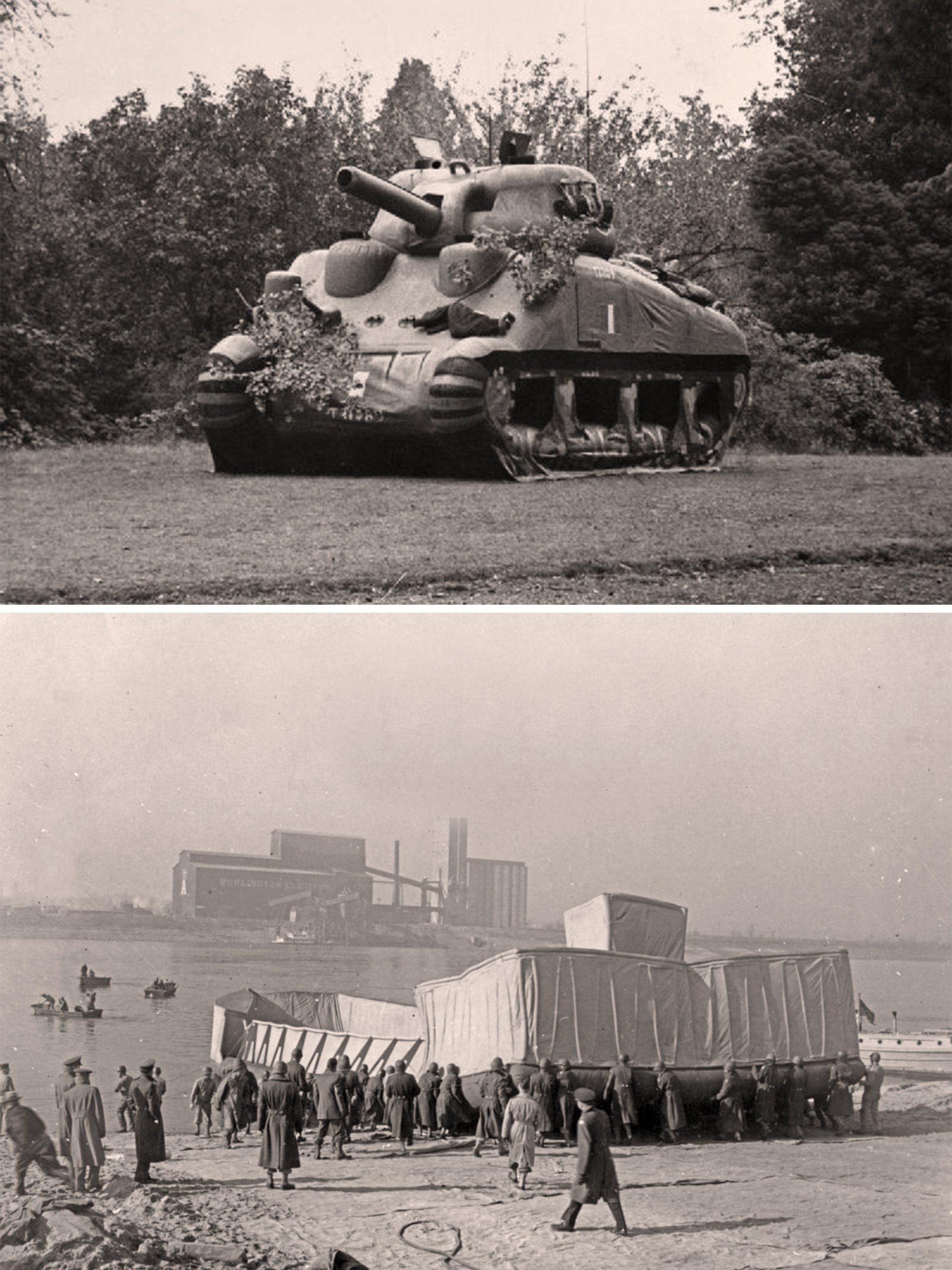

Fortitude operated several different types of deception. It generated artificial wireless traffic that the Germans would be able to intercept, simulating the routine activities of an army training for a combat operation – including exercises, logistics, transportation and road signs. Dummy equipment – tanks, trucks and landing craft were made. These were moved around regularly and occasionally intermingled with real equipment. Double agents “leaked” information back to Germany. Air and combat activity focused on other parts of Europe. For every aerial reconnaissance flight and bombing raid made over Normandy, twice as many missions were flown over the Pas de Calais.

Britain had several advantages in this deception game. For years, MI5, the British security service, had been identifying and capturing German agents sent into Britain. Most had been “turned” – convinced to work for the British and transmit falsified information selected by British intelligence.

In addition, back in Germany, there were several rival intelligence organisations, riven with divisions and with little coherent cooperation or intelligence sharing. In dictatorships, information was power and everyone was vying for the ear of the Fuhrer. Reports from British fake spy networks, including a famous one established by a Spaniard, Juan Pujol Garcia (codename “Garbo”), were avidly consumed by gullible German intelligence authorities, who, ironically, were also paying these non-existent agents. Garbo was prolific with messages and reports to the Germans who believed them entirely.

Since 1941, British encryption specialists at Bletchley Park had managed to crack many German codes. “Ultra” was the name given to this invaluable signals intelligence, which was gleaned from decoding the German Ultra, Lorenz and Hagelin encryption devices. Not only did this intelligence feed tell the Allies what the Germans were doing, it also provided insight into what the Germans thought the Allies were doing.

Finally, German air reconnaissance over the UK was no longer very effective. The Luftwaffe had been driven from the skies. The Germans were always struggling to identify and verify reported concentrations of troops and equipment. Dummy equipment did not always have to be that detailed.

Let’s look at Fortitude North first.

This revolved around the creation of “4th British Army”, a fake army supposedly with an army headquarters in Edinburgh and two corps headquarters in Dundee and Stirling. The supposed mission of 4th Army was an attack on Norway and to try and bring Sweden into the war on the Allies side before pushing into Denmark and driving on Berlin.

The deception activity was almost entirely wireless and double agent driven: no dummy tanks were needed here, because German air reconnaissance was incapable of penetrating to Scotland. Cleverly placed radio traffic details helped convince the Germans this was a real force – The 52nd Lowland Division was understood by the Germans to be ordering skis and crampons for winter operations. In January 1944, British commandos attacked German installations in Norway. The Germans had 13 divisions stationed in Norway – had half of these been transferred to France they could have posed serious problems for an invading force.

But Fortitude South was where the bulk of the deception effort was placed. With the main Normandy invasion force gathering in the south west of England, a fake “First US Army Group” (FUSAG) was being established in Kent and the south east to pose as the main invasion force, aimed at Calais, but later in July, rather than May or June. In actuality, FUSAG had already been set up as a legitimate formation, primarily for administrative purposes, under Omar Bradley. The FUSAG structure was gradually repurposed.

The attention to detail was impressive. Dummy aircraft, tanks, trucks and as many as 250 landing craft were distributed around the fields and ports of south east England. A First Army Group shoulder patch was designed and soldiers made to walk around towns and villages wearing it. Vehicles carried fake symbols and tactical signs. An entirely fictitious 2nd British Airborne Division was created. The BBC was brought in to transmit false details about troop activities.

And, in a stroke of genius, the commander of FUSAG was named as General George Patton – the Allied general that the Germans feared most. Patton’s career was on a knife edge. After controversial incidents in Sicily in 1943, where he had publicly slapped two soldiers and accused them of cowardice, he had almost been sacked. But he was too valuable to the Allies. There was to be a role for him in Normandy. For the moment, however, he had to play the part of the commander of FUSAG, actively and publically inspecting troops in the south east.

Other deceptions were floated around to keep the Germans confused. In May 1944 an actor playing the role of General Montgomery was flown to Gibraltar and Algiers to suggest a landing in southern France. Another implied an Allied landing in the Bordeaux region two weeks after D-Day.

Fortitude succeeded beyond the dreams of the planners. In May 1944, German training exercises were based on the assumption of a landing at Calais.

Bletchley encryption intercepts in early June 1944 showed that Hitler believed that the main effort of the Allies would be at Calais and any Normandy effort would be a distraction. And, critically, the deception was maintained until well after the 6 June landings themselves. When Winston Churchill stood up in the House of Commons to announce the invasion he deliberately said: “This is the first of a series of landings…”

This slowed or prevented crucial German reinforcements arriving in Normandy until it was far too late.

Hitler remained obsessed with Calais and was reportedly still expecting a second invasion there through July and well into August. He was to be disappointed. By then, of course, the battle for Normandy had more or less been decided and the longevity of the Nazi regime was now numbered in months, not years.