The Neo-Freudians and Self-Realization

Neo-Freudian psychologists integrated humanism and existentialism into psychoanalysis.

Neo-Freudian psychologists integrated humanism and existentialism into psychoanalysis.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat motivates human behavior? This was the question that was at the heart of Sigmund Freud’s theory of psychoanalysis. Freud’s answer was that unconscious forces are responsible for the dynamics of mental functioning – unconscious forces that are ultimately rooted in biology.

In psychoanalytic theory, development begins at birth, when the psychic energy, or “libido”, is centered within the baby’s mouth. Different elements of the psyche emerge and develop as the libido is directed towards different parts of the body, and development largely ceases at around age six, at the phallic stage, until the onset of puberty. This is also the stage of Freud’s famous “Oedipus complex”, which arises when the child develops sexual feelings towards their opposite-sex parent, viewing their same-sex parent as a competitor in the battle for attention.

Sexual desire was therefore central to Freudian theory, an idea that challenged the prevailing zeitgeist of the Victorian era, in which sexuality was largely repressed. Freud went so far as to posit that feelings of aggression, envy, and even the creativity betrayed by a magnificent work of art, were manifestations of repressed sexual energy and unfulfilled sexual desires.

Understandably, these ideas were controversial in their time, and remain that way today. Nevertheless, at the turn of the 20th century, it seemed that Freud was onto something of considerable importance, in his emphasis on the unconscious influences of the personality. His work has since spawned an endless stream of new ideas that seek to integrate classical psychoanalytic theory with a more holistic and well-rounded view of human psychology.

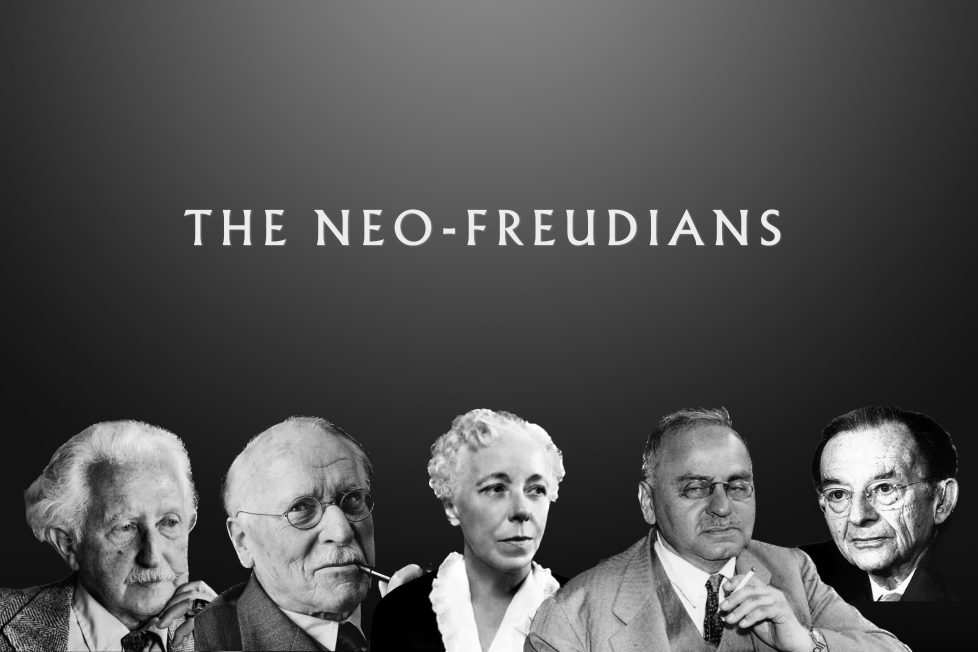

The neo-Freudians were a group of psychologists that emerged in the wake of Freud around 1940. Central to their contributions to psychoanalysis was a re-emphasis on the ongoing process of psychological development throughout an individual’s life. While Freud’s theory of psychic development entailed that the psyche became fixed in its basic form by the phallic stage, and thus that the psyche was largely unable to escape its childhood influences, the neo-Freudians were driven by a humanistic vision of human dignity and potential. Thus, many of the new developments were heavily focused on personal growth and self-realization, and the reformulation of psychotherapy into a more compassionate practice.

Freud had also attempted to root his ideas securely on the bedrock of human biology, yet this led him to place less emphasis on the importance of culture and society in shaping human behaviour. By 1940, the ideas of the early existentialist philosophers, such as Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, were exerting their influence on the culture at large, and a new generation of existentialists, including Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre, emerged contemporaneously with the neo-Freudian movement.

Existentialism, naturally, is concerned with the nature of human existence and freedom, emphasizing the importance of taking responsibility in one’s life. For psychotherapy, this meant taking ownership of negative feelings, attempting to transform them into a force for good, rather than suppressing them.

In the following article, we shall explore some the key ideas of the major contributors to neo-Freudian theory.

Carl Jung and Alfred Adler were students of Freud at the Psychoanalytic Society in Vienna and began to diverge from Freudian theory at a relatively early stage in their careers, taking particular issue with Freud’s emphasis on the importance of sexuality.

By the 1910s, both Jung and Adler had developed their own, largely unique, theories of psychoanalysis (analytic psychology and individual psychology respectively), which have spawned their own networks of followers, critics, and neo-theorists. It is therefore, in a strict sense, inappropriate to refer to them as “neo-Freudians”. Nevertheless, they played an important role in the development of psychoanalysis, despite the fact that Freud wrote several scathing papers altogether denying their relation to his newly developed field.

The unconscious mind, for Jung, is much more than a repository of repressed sexual urges. Rather, it is a wellspring of creativity and potential that presents to the individual a path towards wholeness and integration. Jung’s unconscious far exceeds the biological forces of the individual, involving the entire cultural history of the species.

There is thus a shared aspect to the unconscious, which is constituted of archetypal symbols that become formed over thousands of years of evolution. Notable examples of these symbols include the mother, the hero, and the shadow, which reveal themselves in the dreams and myths of cultures from across the globe.

This “collective unconscious” influences our beliefs and behaviors just as much as does our biology, so that the individual is not as sheltered from societal forces as Freud had wagered. Through an understanding of the role that the archetypes play on a collective level, we can begin to understand what motivates our likes, dislikes, gifts, and torments, as individuals.

“Individuation” was then the process of integrating aspects of the personality, and Jungian archetypal traits, that had become repressed through the unconscious mind’s attempt to protect the ego from traumas and unfulfilled desires. The goal is simply growth, and so it is here that we begin to see the importance of personal responsibility that betrayed the existentialism and humanism implicit in many neo-Freudian theories.

Alfred Adler also placed great importance on responsibility in the ongoing process of personal development. However, he saw that society and culture played a critical role in shaping this development. While the influence of culture for Jung was mediated via the archetypes of the collective unconscious, for Adler, individuals are largely influenced by their subjective perceptions of their place within a larger community.

These perceptions inevitably lead to a comparison between oneself and others, and this fosters a sense of inadequacy and inferiority. In turn, these feelings fuel the drive to achieve a higher status in that society. Yet, Alder did not see this as a negative thing, but as an essential facet of human experience that should be embraced. It is precisely in one’s interest in society and community that the desire for self-improvement is facilitated.

Adler was deeply influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche and his concept of the “will to power”, which refers to the natural human desire to gain control over one’s environment. In individual psychology, the “will to power” becomes the “striving for superiority”. Nevertheless, Adler also recognized the danger of corrupting the striving for superiority, and emphasized that healthy striving is that which is socially constructive. His “superiority complex”, conversely, is distinct from normal striving, as it arises from the overcompensation of feelings of inferiority, and can be socially destructive.

Individuals only gain a sense of self-worth insofar as they also value others, and they realise their own potential insofar as they positively contribute to the world around them. Both of these things help to cultivate a sense of belonging within a community, and this leads one to recognize that one’s actions make a real difference in the world, which leads to a sense of fulfillment and meaning. As such, the inferiority complex arises precisely because one’s subjective perceptions convey a disconnection from other individuals.

The following three theorists can be placed more securely within the neo-Freudian movement. Erik Erikson diverged from Freud in his emphasis on the role of the ego in the development of personality. Whereas Freud described the ego as the mere mediator of the id – the primitive and instinctual part of the psyche – and reality, Erikson affirmed that the ego played a much more active role in ruling and shaping one’s identity. He posited that the personality develops through eight distinct stages, each of which is marked by a different psychological crisis that must be overcome.

First is the stage of trust vs. mistrust, in which the infant must learn to trust the world around them. Success in this stage depends on the care of the mother, which fosters the virtue of hope.

Second is the stage of autonomy vs. shame, in which the toddler must learn to establish a sense of independence and temperance. Success in this stage depends on parents allowing the child to do things “all by themselves”, which fosters the virtue of will.

Third is the stage of initiative vs. shame, in which the pre-schooler must continue to develop their sense of independence. Success in this stage depends on the child’s ability to make their own decisions, which fosters the virtue of purpose.

Fourth is the stage of industry vs. inferiority, in which the school-age child must learn to recognize the differences between themselves and others. Success in this stage depends on the child’s friendships and school environment, which foster the virtue of competence.

Fifth is the stage of identity vs. role confusion, in which the adolescent begins to reflect on their sense of self, beliefs, and values. Success in this stage again depends on the parents in allowing the teenager sufficient freedom, which fosters the virtue of fidelity.

Sixth is the stage of intimacy vs. isolation, in which the early adult starts to think about other people in the world, including romantic relationships. Success in this stage depends on the ability to form lasting bonds with others, which fosters the virtue of love.

Seventh is the stage of generativity vs. stagnation, in which the middle adult forms a desire to contribute towards society. Success in this stage depends on a belief in the next generation, which fosters the virtue of care.

And finally, eighth is the stage of ego integrity vs. despair, in which the late adult comes to terms with the course of their life. Success in this stage depends on the acceptance of unfulfilled desires, which fosters the virtue of wisdom.

Erikson’s psychology is characterized by an optimistic view of human potential, which contradicted Freud’s more pessimistic emphasis on the events of early childhood in determining the course of adult life. For Erikson, identity is not fixed but constantly evolving, and everyone is able to gain a sense of purpose and fulfillment in life.

Karen Horney was the founder of feminist psychology, which she developed as a direct response to Freud’s ideas regarding sexuality and gender. As she saw it, Freud’s theories were predicated on the social experiences of males and were therefore insufficient in addressing those of women. Nevertheless, she accepted the bulk of Freudian thought, and strove to reformulate psychoanalysis into a more humanistic theory, which acknowledged how different cultural norms resulted in different psychosocial problems.

Freud theorized that as young girls begin the transition to womanhood, their prior attachment to their mother becomes transformed into a competition with the mother for the affection of the father. This process is the female manifestation of the Oedipus complex, referred to as “penis envy”, insofar as it involves the perceived biological superiority of men.

Horney disagreed with this analysis, arguing that women’s feelings of inferiority were largely the result of societal influences and that Freud’s perspective was owed to his own cultural biases. These influences arise from the greater value that society places on the accomplishments of men, and the cultural expectation that women should be dependent on men.

Horney’s humanistic focus on societal and cultural forces as the major determinants of personality development subsequently informed her mature theories of neurosis and self-realization. She posited that individuals often develop one of three methods of dealing with the social pressures and stresses of life – narcissism, perfectionism, and arrogant-vindictiveness. In each case, individuals have formed an idealized vision of their self, and see that their real self does not live up to these expectations. The real self is thus degenerated into a “despised self”, leading to the imagination of unrealistic goals and feelings of self-hate.

Nevertheless, the continual self-comparison between the real self and the ideal self, which Horney referred to as the “tyranny of the shoulds”, can be used as a powerful tool for growth. When one accepts their self as it is, the previously corrupting force of an unattainable ideal becomes a facilitator of the ongoing process of self-realization. Horney repeatedly stressed that this process is fundamentally reliant on the cultivation of self-awareness, which is the principal task of the psychotherapist. By identifying one’s genuine values and passions, and by celebrating one’s unique talents and qualities, individuals are able to develop a more realistic and productive self-identity.

Erich Fromm was a close collaborator of Horney and shared the latter’s combination of respect for Freud’s accomplishments, and condemnation of his culturally ingrained misogyny. Fromm was particularly interested in socio-political psychology, arguing that the structure of mid-20th century society propagated feelings of detachment and alienation in its citizens. He was deeply inspired by the works of Karl Marx, which he interpreted from a strictly humanist perspective, becoming an early promulgator of Marxist humanism.

Fromm recognized that modern society demanded that individuals take responsibility for their own lives, and posited that this freedom of will is, for many people, a source of overwhelming uncertainty and anxiety. Accordingly, individuals inevitably seek what he termed an “escape from freedom” and the anxiety brought with it. This commonly involves aligning one’s idealized self with the expectations of society (automaton conformity), submitting to external forms of authority (authoritarianism), or directly confronting and conflicting with others or the world in general (destructiveness).

However, Fromm also believed that when we embrace our freedom, it is then a force for good, and he explored ways in which individuals could rise above their feelings of alienation and reach a state of “biophilia” – the love of life in all its forms. For Fromm, one develops a sense of belonging and meaningful connection as one fulfills a number of basic needs. These needs include accomplishment, oneness with nature, striving for a goal, understanding one’s place in the world, a sense of identity, rootedness in the outside world, and creative expression.

Central to the process of reconciliation is the active expression of love, which Fromm interpreted as a constructive force that facilitates interpersonal connections, and much more than an emotion. Love involves both the willingness to be vulnerable and share one’s experiences and struggles, and, reciprocally, being open and attentive to the vulnerability of others. The openness required for the exercise of this creative capacity to love also requires the individual to become aware of their limitations, which helps them to form a healthier and more self-aware identity.

The theorists discussed so far are but some of the most immediate successors to Freud, yet there have been many approaches to psychoanalysis that have emerged in the decades that followed. Many of these have been similarly considerate of the social and cultural factors that shape the personality, in addition to the unconscious.

Erik Erikson’s ideas contributed to the formation of “ego psychology”, which began with Freud’s daughter, Anna, and was developed further by Heinz Hartmann. Ego psychology would emphasize the power of the conscious ego in overcoming the sources of neurosis that Freud had isolated in the unconscious.

Another neo-Freudian, Harry Stack Sullivan, initiated a line of thought that later became “object relations theory”, which addressed Freud’s theory of psychodynamics. Instead of the biologically fixed process of libido localization, the object relations theorists asserted that the interpersonal relationships between the child and its caregivers were the major moulder of human behavior.

The emphasis on humanism also continued to develop outside of the strict sphere of the neo-Freudians. Abraham Maslow, a student of Adler, went on to develop “humanistic psychology” with Carl Rogers. The former also formulated a hierarchy of innate human needs that culminated in “self-actualization”, while the latter developed a form of psychotherapy called “person-centered therapy”, which reframed the emphasis from unconscious conflicts back to conscious experience, self-awareness, and personal growth. Both of these were in part a response to the hard-handedness of Freudian analysis.

Further still, there is “logotherapy”, developed by another of Adler’s students, Viktor Frankl, who is best known for his book on Nazi concentration camps, Mans Search for Meaning. Whereas Freud utilized the Epicurean idea of the “will to pleasure”, and as Adler used the Nietzschean idea of the “will to power”, Frankl’s logotherapy was based on the Kierkegaardian idea of the “will to meaning”. He thus emphasized the importance of acquiring meaning and purpose in life as a way to rise above the psychological conflicts that would be tackled directly in psychotherapy.

And finally, though like Frankl he is not strictly a neo-Freudian, it is worth mentioning Jacques Lacan, who famously proposed a “return to Freud”, challenging both ego psychology and object relations theory. Lacan felt that the incorporation of humanism into psychoanalysis was dragging the field towards self-help, and away from science. Despite his claims of returning to Freud, however, Lacan’s theory diverged from traditional psychoanalysis relatively significantly. Inspired by the structuralist movement, Lacan believed that the unconscious was structured like a language and that this “symbolic order” was responsible for the shaping of the self, in place of biological instincts.

The neo-Freudians recognised the inadequacies in Freudian theory in addressing the positive aspects of personality development. They sought to incorporate humanism and existentialism into new forms of psychoanalysis, focusing on self-awareness, personal development, and individual experience, and less on unconscious conflicts.

However, while humanistic and existential forms of therapy are still practiced, psychoanalysis, in general, has become overshadowed by the fields of cognitive psychology, behaviorism, and psychopharmacotherapy. These fields are inherently better equipped to integrate with the scientific method, which has brought them favor over the talk therapy approaches whose effectiveness is more difficult to empirically quantify.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy was introduced in the early 1960s, and the widespread use of antidepressants soon followed. Nevertheless, these new, affordable, forms of treatment are primarily oriented towards symptom reduction, often leaving the underlying issues that contribute towards neurosis unaddressed. Fortunately, there are indications of a resurgence of traditional therapies. The growing interest in mindfulness and meditation is grounded on the same basic principle as many neo-Freudian therapies – the cultivation of self-awareness – and there is ongoing research in the field that will help us to better integrate psychotherapy within the scientific method.