Futurism in Art: Who Gets to Write Our Futures?

The Futurist movement lived through many faces and controversies during its 100-year history.

The Futurist movement lived through many faces and controversies during its 100-year history.

Table of Contents

ToggleIn the early days of the twentieth century, a group of young Italian artists led by the scandalous poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti published a remarkable and bitter text filled with bloodlust, calls to violence, and praise of technology turned into ecstatic fetishism. They called for his followers to worship speed and motion, claiming that a racing motor car would trample the beauty of any antique sculpture.

They called themselves Futurists. In dozens of texts that followed they would explain in detail how the new world should be tailored to their beliefs. Eager to get rid of anything old, he called for the destruction of museums, libraries, and other depositories of accumulated knowledge. All outdated artworks required immediate annihilation, with Futurist works not being exceptions: future generations of artists were expected to treat the creations of Marinetti and his followers similarly.

Soon, the word Futurism traveled through borders and cultures, settling in a pre-revolutionary Russian Empire. Devoid of the original Italian context, it would take surprising and often unexpected forms in other countries. Russian and Ukrainian Futurisms, for instance, mostly relied on folk art and legacy in their works, to the great confusion of their Italian counterparts.

Years later, Futurism became a common topic for mass-cultural products associated not with a particular artistic group but with the genre of imagined futures as such. But who and how gets to invent our future, and why do some hypothetical utopias leave a bad taste in your mouth?

Loud, radical, and shocking opinions of the Italian Futurists did not occur without political reason. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Italy had just overcome a long period of volatility, with the unification of the country happening only in 1848. Distressed by constant inner turmoil and territorial disputes, the country could not compete with other European superpowers. For the rest of the continent, the country was hardly more than a giant open-air museum filled with remnants of the Roman past. Thus, Marinetti’s contempt for everything traditional was the direct result of the country’s fixation on its past without looking into the future.

The paradox of Futurism was that while claiming to start a revolution in art, the movement’s evangelists prioritized ideology over visual language. By the time Marinetti’s manifesto had reached its audiences and caused an uproar, Futurist painting was still mostly dependent on Impressionist and Pointillist techniques, playing with light effects or applying small brushstrokes of unmixed color. It all changed after Gino Severini and a group of other Futurist painters visited Paris to see early Cubist works. Impressed by the new bold and aggressive style, they nonetheless quickly grasped its weakest spot: Cubism was immobile, rigid, and devoid of dynamism. While demonstrating its objects from several angles at once, it did not interact with space and time.

Thus, the Futurists found the visual expression of their ideas: their art had to express movement, dynamism, and speed in the same manner the new technology did. The prime target was not the object itself but its relationship to the environment around it. The main instrument for it was the so-called linee forza – ray-like lines, dotted or solid, expressing the distortion of space around the moving object. Futurist characters had multiple legs and heads, cutting through space around them and being observed at all stages of movement at once.

The initial excitement and emotional intensity did not last long. Soon after World War I, so much anticipated by the Futurists, most followers of Marinetti burnt out and wasted their militarist potential. Some artists, like Giacomo Balla, the oldest and the most successful of Futurists, publicly denounced the movement and returned to traditional oil painting. A brief revival happened in the 1930s when the newly available technology of airplane transportation propelled the new type of art. Aeropittura, or aeropainting, focused on aerial landscapes, airplane mechanisms, and the unity of a pilot with his machine.

One of the particularities of the European artistic scene in the early twentieth century was the astonishing amount of theoretical and conceptual work concerning art, its ideologies, and its visual language. The pressing need to invent a new way of expression turned into competition, with new theories emerging almost every day. Most of them were borderline nonsensical and relied on shock value more than on actual applicability.

The phenomenon of Russian Futurism, built mostly by Russian and Ukrainian artists and poets, was in many ways paradoxical. While Marinetti’s manifesto focused on overthrowing the legacy of the Roman empire, some Russian Futurists found expressive potential in folk art and tradition. In fact, in Russia, Futurism became a fashionable synonym for the word avant-garde and gathered under its umbrella a series of art movements such as Constructivism, Neo-Primitivism, Rayonism, Suprematism, and others. The future was unclear but exciting, and everyone had an option to offer.

Unlike Italian art, Eastern European Futurism was visually and stylistically diverse and ranged from complete non-representative paintings of Kazimir Malevich to stylized portraits of peasants and workers by Natalia Goncharova. Some traces of Italian influence remained in conceptual frameworks: Mikhail Larionov’s art theory of Rayonism was essentially the same as the concept of linee forza, tossed with pseudoscientific commentary on physics, waves, and radioactivity.

The early decades of Futurism were deeply rooted in political controversies. As a politically charged and radical movement, it overlapped in its development with the rise of two totalitarian regimes on opposite sides of the political spectrum.

From the earliest days of Italian Futurism, its aggressive, militarist rhetoric of wiping out the past to build a new progressive Italy lined up with the rising fascist ideology. This violent masculinity brought demise to the most talented and promising young artists of the group. As World War I erupted, many young Futurists readily enlisted, welcoming the bloodshed. Sculptor Umberto Boccioni and architect Antonio Sant’Elia died during military action, while many others, including Gino Severini who avoided service, were disappointed in the movement after seeing their militarist principles becoming reality.

Marinetti, however, was thriving. Not only would he volunteer to fight in both world wars – but he would also become closely affiliated with the leader of Fascist Italy, Benito Mussolini. Marinetti’s ambition was to make Futurism the official art style of Mussolini’s regime, yet the leader was too cautious to focus all his attention on one particular group. He understood the importance of art as a propaganda tool and preferred to pay equal attention to the majority of artists. However, on at least one occasion Mussolini protected the Futurists from public outcry. In 1938, Nazi German authorities arranged a traveling exhibition of avant-garde works called Degenerative Art, aimed at defaming non-representational art and proclaiming the supremacy of traditional painting. The show featured a selection of Futurist works as well, so Mussolini strictly forbade it from touring Italy.

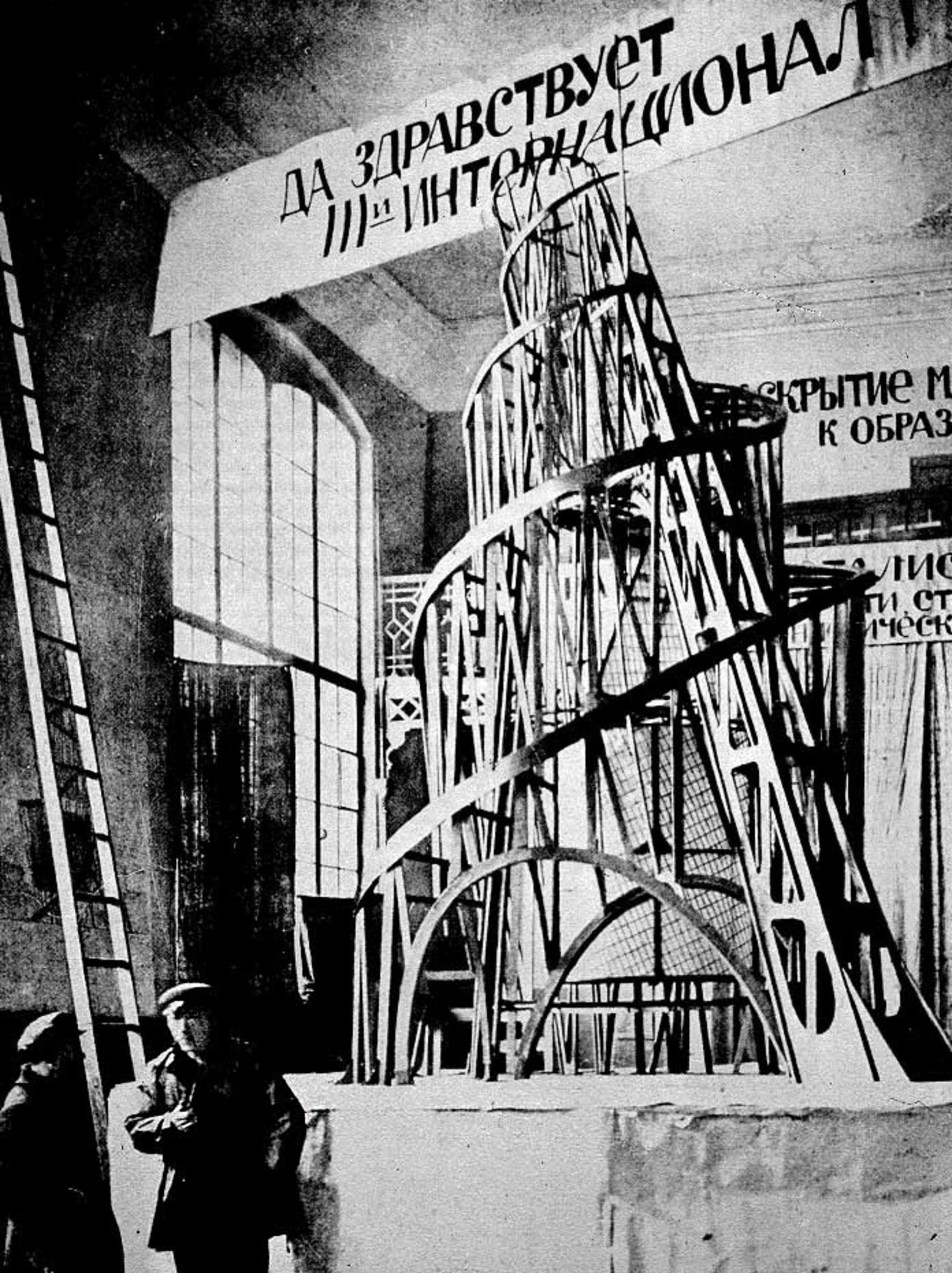

The Russian brand of Futurism was essentially left-wing and shared a brief yet remarkable moment of unity with the newly emerging Soviet authorities. The early days of the Soviet Union were marked with an ambition to revolutionize every sphere of human existence: from work to family life, the new power was equally enthusiastic about mechanization of labor and sexual liberation. Many Futurist artists were enchanted by this promising new world. One of the most prominent artifacts of the era was the monumental project of Tatlin’s Tower. Vladimir Tatlin designed a rotating monument 400 meters tall, with conference venues and offices on its numerous levels. The ambitious project was never built but remained a monument to dream, dedication, and – frankly – sheer absurdity.

Most Futurist artists left the Soviet Union soon after its emergence, while others preferred to work for the government. The collaboration, however, did not last long: soon the new authority realized that the boldness and loudness of the Futurists could turn into a threat at any given moment. The progressive and ambitious ideas of the early Soviet thinkers quickly gave way to growing conservatism. One of the leaders of the Russian Futurist movement, poet Vladimir Mayakovsky was among those discarded by his audience: after years of working in propaganda and advertising, he was publicly ridiculed and denied publication, which resulted in his suicide in 1930.

In the 1960s, the world once again became obsessed with the future. Space exploration triggered the rise of science fiction media, which mostly centered around Western culture and Western scientific development. Around that time, the audiences started to realize how exclusive visions of the future are. Western-dominated Futurism of the past left little space for people of color, cultural diversity, and multifaceted perspectives. This realization led to the emergence of a new branch of future-centered art – Afrofuturism.

Afrofuturist art often envisions figures of aliens, human-animal hybrids, or pieces of technology based on the cultural and historical heritage of the African continent. By doing so, it adds people of African descent into the imaginary future that would overcome the aftermath of slavery and racial and cultural discrimination.

The problem with Futurism in its original sense is that it was by definition exclusive: by writing a utopia for some, its proponents inevitably constructed a dystopia for others. Antonio Sant’Elia’s building designs, created simultaneously as a functional solution and a celebration of the new era, incarnated themselves not in modern Italian cities but in the fantastic dystopian films, including the legendary Metropolis by Fritz Lang. Lang used Sant’Elia’s blueprints to construct a place filled with suffering and exploitation, with the rich enjoying their lives on top of the sky-piercing towers. The Futurist future looks bright, but it rarely comments upon those who build it behind the scenes and certainly does not warn you that not everyone is allowed to experience it.