13 Salvador Dali Paintings Every Art Lover Must Know

Explore 13 masterpieces by Salvador Dali that show his unique creativity and artistic vision.

Explore 13 masterpieces by Salvador Dali that show his unique creativity and artistic vision.

Table of Contents

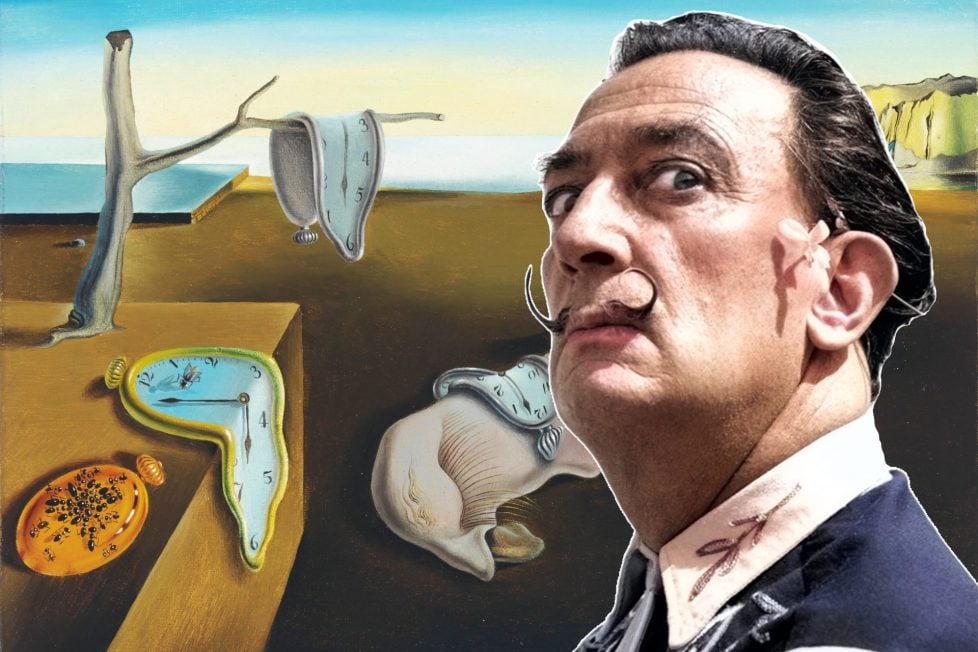

ToggleIn the realm of art, few figures have captured the human imagination quite like Salvador Dali. Born on May 11, 1904, in the quaint town of Figueres, Spain, Dali would grow to become a pivotal figure in the Surrealist movement. His paintings, enigmatic and surreal, are imbued with dreamlike landscapes punctuated by bizarre, fantastical objects—a product of his distinctive ability to paint dream and reality on the same canvas.

A master of depicting his own fears and fantasies, Dali’s exploration of psychological themes and his knack for self-expression set him apart from his contemporaries. His works invite us into his world, a realm where reality bends and distorts, and nothing is as it seems.

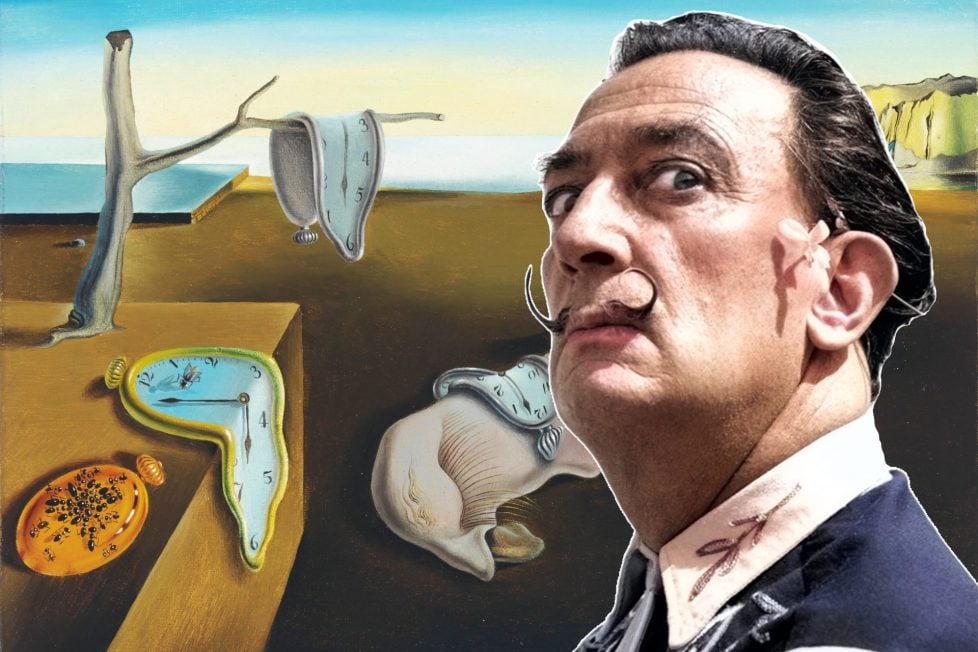

One can’t delve into Salvador Dali’s works without first pausing at his iconic painting, “The Persistence of Memory”. This piece is a quintessential representation of Dali’s exploration of the fluidity and irrationality of time. It features limp, melting watches that seem to defy the laws of physics, challenging traditional views of time as fixed and orderly.

Dali’s use of “soft” watches was influenced by Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity, an insight that transformed our understanding of time and space. In this disconcerting landscape, time doesn’t merely tick away—it bends, melts, and even decays. The ants crawling over the pocket watch, a symbol of decay or a fear of infestation, is a reflection of Dali’s personal anxieties.

The backdrop of the painting, a rugged landscape bathed in the warm glow of sunset, is a reminder of Dali’s connection to his birthplace, Catalonia. This landscape often appears in his works, a symbol of his roots and a link to his personal history.

A distinctive element in the painting is a distorted, sleeping face, often interpreted as a self-portrait. This recurring motif in Dali’s work amplifies the dreamlike ambience, suggesting an introspective journey into the artist’s subconscious mind. The face’s tranquil rest contrasts the bizarre melting clocks, creating a dissonance that is quintessentially Dali.

“Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War)” is one of Dali’s most politically charged artworks. Painted in 1936, mere months before the onset of the Spanish Civil War, it serves as a foreshadowing of the impending disaster.

The grotesque, twisted creature that dominates the canvas is a ghastly embodiment of the effects of civil conflict. It is a disturbing depiction of self-destruction, evoking the horrific vision of a nation tearing itself apart from internal strife. This theme aligns Dali’s painting with Picasso’s “Guernica”, another iconic anti-war painting that represented the same historical event.

Dali’s incorporation of boiled beans, a humble staple of Catalan cuisine, adds relevancy to the painting. The beans seem to suggest the profound ways in which war infiltrates and disrupts everyday life. Yet, they also add an element of absurdity, further emphasizing the irrationality of war.

Though Dali often claimed to be politically indifferent, this painting is a departure from his usual apolitical stance. It shows how, despite his eccentricities, Dali was deeply affected by the world around him. “Soft Construction with Boiled Beans” remains one of Dali’s most powerful paintings, a reminder of the devastating consequences of civil conflict.

Dali’s exploration of the world of dreams and the unconscious reached a zenith in his painting “Sleep” (1937). Here, sleep is personified as an amorphous entity, precariously supported by crutches—a representation of Dali’s fear of the unknown horrors lurking in the unconscious mind.

The desolate landscape in the painting amplifies the eeriness of the scene. This desolation is reminiscent of the landscapes painted by Giorgio de Chirico, an artist whose metaphysical works greatly influenced the Surrealists. The sense of solitude conveyed by the empty landscape focuses the viewer’s attention on the monstrous face, indicating the isolation often experienced in dreams.

The motif of crutches appears in several of Dali’s paintings. This could be traced back to the 16th-century Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch, whom Dali greatly admired. Bosch’s “Beggars and Cripples” features numerous figures supported by crutches, and this could have inspired Dali’s to use this peculiar motif.

Despite its seemingly simple composition, “Sleep” is a complex commentary on the relationship between consciousness and the unconscious. It demonstrates Dali’s mastery of the uncanny, a trait he shared with fellow Surrealist René Magritte. However, Dali’s hyper realistic portrayal of dream imagery gave his work a unique edge.

“The Burning Giraffe” is one of Dali’s most prominent works, painted during the twilight of the Spanish Civil War in 1937. The painting vividly embodies Dali’s concerns about war and destruction, specifically the looming specter of World War II, which he described as the “masculine cosmic apocalyptic monster”.

The painting’s titular burning giraffe is an image that is both disturbing and surreal, which Dali interpreted as a premonition of war.

The feminine figures with drawers in their bodies suggest Dali’s interest in Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis—specifically the idea of the unconscious mind being a repository of secrets and concealed desires. Freud’s influence on Dali and other Surrealists cannot be overstated. They saw in Freud’s theories a scientific validation of their own explorations of dream states and irrationality.

The painting’s arid backdrop echoes Dali’s beloved Catalonian landscapes, hinting at his personal and political themes. The long, spindly legs of the giraffe, standing vulnerable amidst chaos and turmoil, represent the fragility of civil society in the face of war.

“Swans Reflecting Elephants” is a fascinating example of Dali’s mastery of double imagery, a technique that became a staple in his artistic repertoire. The painting features a serene landscape with three swans on a tranquil lake. But in their reflections, the graceful swans morph into weighty elephants, creating a surreal transformation that challenges the viewer’s perception of reality.

This powerful illusion showcases Dali’s ability to distort reality intentionally. It’s a reflection of his “paranoiac-critical method”, a process he developed where he would induce a paranoid state in himself to create multiple images out of one and the same configuration. This method was Dali’s unique contribution to Surrealist techniques and was greatly admired by his contemporaries, including the influential Surrealist André Breton.

Despite the contrast between the swans and elephants in terms of gracefulness and weight, Dali’s surrealist imagination connects them effortlessly, blurring the line between reality and illusion. The serene landscape in the painting, juxtaposed with the eerie transformation happening in the water, highlights Dali’s propensity to merge the mystical with the mundane.

The concept of multiple realities presented in this painting is not exclusive to the realm of art. It finds parallels in the field of quantum physics, where the superposition principle postulates that any two (or more) quantum states can be added together. This connection between art and science is an indicator of Dali’s broad intellectual curiosity.

“Metamorphosis of Narcissus” is an example of Salvador Dali’s affinity for mythology and his ability to weave these ancient tales into his surrealistic tapestry. The painting is based on the Greek myth of Narcissus—a beautiful young man who falls in love with his own reflection, ultimately transforming into a flower bearing his name. This mythological narrative serves as a conduit for Dali’s exploration of themes such as vanity, self-obsession, and the ephemerality of beauty.

The painting employs the “double image” technique, where two images are depicted using the same elements. The hand holding an egg and the flower mirrors the shape of the kneeling Narcissus, creating an optical illusion that challenges the viewer’s perception. This technique can be seen as an artistic manifestation of the “paranoiac-critical method”, further enhancing the painting’s surrealistic quality.

The egg from which the flower sprouts is a symbol of new life, suggesting the cyclical nature of existence—a theme that aligns with the philosophical teachings of ancient Greeks. The two figures, one solid and the other fluid, reflect Dali’s unique understanding of the duality of human nature. This duality is reminiscent of the philosophical concepts of Heraclitus, a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher, who posited that existence is characterized by a constant state of flux.

The chessboard in the background represents the strategic play inherent in any love affair, adding a layer of intellectual calculation to the emotional narrative of the myth.

By integrating classical mythology with his unique surrealist style, Dali’s “Metamorphosis of Narcissus” presents a compelling blend of the ancient and the modern.

“Geopoliticus Child Watching the Birth of the New Man” (1943) is a departure from Dali’s earlier works. Here, Dali moves away from the purely psychological realm towards a broader geopolitical commentary. The painting is a portrayal of a new world order emerging.

The central figure, a man emerging from an egg, symbolizes the birth of new possibilities. This image is watched by another figure—representing humanity—observing these geopolitical shifts. The egg motif, prevalent in many of Dali’s works, suggests themes of birth, renewal, and fragility, which are aptly reflected in this painting’s context.

The geographical form is reminiscent of a map, placing the image in a global context. This could be seen as Dali’s commentary on the global nature of World War II and its far-reaching implications. The protective hand reaching in from the left represents the responsibility of current generations towards the future, an apropos sentiment considering the painting’s wartime context.

The painting’s symbolism and themes find parallels in the works of other artists grappling with the geopolitical upheavals of the time.

“Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening” is a great example of Dali’s dreamscapes that depict complex themes of fear, attraction, and surreal scenarios. Painted in 1944, this piece is a fascinating dive into Dali’s surrealist imagination and his mastery of narrative devices.

The painting depicts a sequence of events—a narrative device Dali referred to as the “sequence of desire”. The sequence begins with a bee flying around a pomegranate and culminates with tigers leaping out towards a woman, suggesting the anticipation and hunger for what one is chasing. This depiction finds parallels in early Greek vase paintings, which also used narrative sequences to tell their stories.

The pomegranate in the painting is a symbol of fertility and abundance, reflecting Dali’s personal associations. This symbol also appears in classical mythology, most notably in the story of Persephone, who was condemned to spend part of each year in the underworld after consuming pomegranate seeds.

The bayonet-shaped elephant, a hallucinatory image typical of Dali’s paintings, symbolizes distorted reality, while the aggressive scene of tigers jumping towards the woman mirror Dali’s fears and anxieties. The painting can be seen as an exploration of Freud’s theory of dream interpretation, where dreams are understood as wish fulfillment.

In “The Elephants” (1948), the elephant, a frequent figure in Dali’s work, becomes a symbol of paradox. Depicted with elongated, thin legs, the elephant in Dali’s imagination symbolizes fragility despite its typical association with strength and size. This contrast reflects Dali’s desire to challenge and subvert conventional symbolism.

The elephant in this painting carries an obelisk on its back. The obelisk, a symbol of historical knowledge, represents the weight of the past—a burden that society carries forward through time. This motif finds echoes in ancient Egyptian culture, where obelisks were considered sacred.

The barren landscape and backdrop of mountains mirror Dali’s own homeland of Catalonia. This setting, familiar from many of Dali’s paintings, speaks to the artist’s deep connection to his place of birth. The desolate landscape also serves to intensify the dreamlike atmosphere, a hallmark of Dali’s surrealist style.

In a broader sense, the painting can be seen as a commentary on the human condition—our strengths and weaknesses, the weight of our history, and our dreams and realities.

“Leda Atomica” marks a significant shift in Dali’s approach to painting. Moving towards a more classical style while maintaining his dreamlike substance, this painting reflects Dali’s evolving artistic vision in the late 1940s. It’s based on the myth of Leda and the Swan, a recurring theme in Western art, maintaining Dali’s fascination with mythology.

The painting’s name, “Leda Atomica”, is a reference to atomic energy, indicating Dali’s evolution towards “Nuclear Mysticism”—a philosophy where he combined Catholicism, Mathematics, and nuclear physics. Dali’s exploration of nuclear physics was influenced by the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the groundbreaking scientific advances of his time.

In the painting, Dali carefully positions Leda’s (who is a depiction of his wife, Gala) body and legs suggestive of an atomic whirl, mirroring the scientific theory of atomic particles swirling around a dense nucleus. The floating objects, defying gravity, correspond to Dali’s interest in the world of quantum physics where traditional laws of gravity don’t apply. This thematic focus on the atomic and the molecular resonates with the scientific milieu of the mid-twentieth century.

This painting underscores Dali’s relevance as an artist who continually evolved and pushed the boundaries of art and perception.

“Galatea of the Spheres” (1952) continues Dali’s artistic journey into the realm of science. The painting presents a portrayal of his wife Gala, depicted as an assortment of spheres. This composition reflects Dali’s understanding of atomic theory, where particles and energy are the fabric of existence.

The proximity of the spheres in the painting convey his belief in the unity of the universe, arguing that all matter is interconnected. The painting’s abstraction, with the absence of limbs or any other distinctive feature apart from the face, emphasizes the universality of the atomic theme. By breaking down Gala’s figure into smaller parts, Dali might also be commenting on the infinite divisibility of matter—a concept that resonates with Zeno’s paradoxes, which grappled with the concept of infinite divisibility.

“Galatea of the Spheres” is a captivating fusion of art, science, and philosophy.

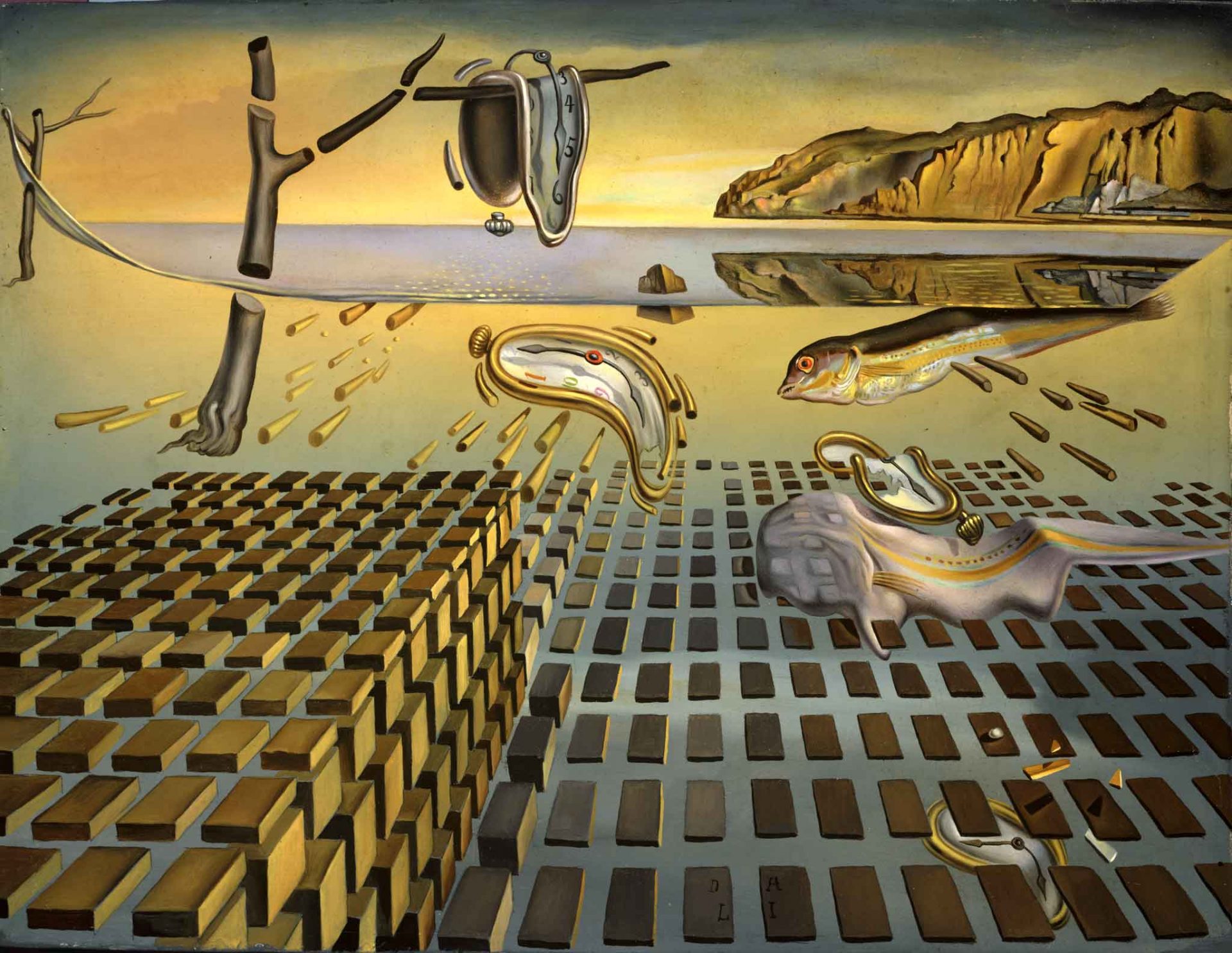

In “The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory” (1954), Dali revisits his iconic “Persistence of Memory”, offering a fresh perspective on the timeless classic. As with the previous two paintings, this piece demonstrates Dali’s fascination with Nuclear Mysticism.

The disassembled landscape reflects Dali’s interest in the atom. The melted watches, once solid and material, now float over segmented blocks—indicating the breakdown of cohesive reality in the face of physics’ revelations about the atomic world.

A fish, a recurring motif in Dali’s works, symbolizes life and fertility. This symbolism finds echoes in various cultures around the world, from the early Christians to Indian mythology. The painting can also be interpreted as Dali’s contemplation over his own artistic evolution, the changing times, or an exploration of the continuity and disintegration of memory.

In “The Sacrament of the Last Supper” (1955), Salvador Dali explores the sacred narrative of Christ’s final meal with his disciples. This piece represents Dali’s pivot towards spirituality and his approach to religious art, merging classical themes with Surrealism.

The central figure of Christ, rendered with a spectral transparency, transcends the traditional depictions of the divine. This otherworldly portrayal reflects Dali’s metaphysical exploration of spirituality, a divergence from the physical solidity usually associated with Christ in religious art.

The painting’s framework is a dodecahedron, a geometric form with twelve faces, each a pentagon—a shape Dali associated with the divine. This usage is an instance of Dali’s fascination with sacred geometry, a concept finding roots in the ancient belief that geometric shapes have supernatural meaning. Here, the twelve faces of the dodecahedron mirror the twelve apostles, bringing together geometry, numerology, and theology in a fusion typical of Dali’s artistry.

Salvador Dali’s contribution to Surrealism remains unrivaled due to his ability to seamlessly blend hyperrealism with dream-like sequences. His masterful control over various painting techniques, his penchant for eccentric themes, and his flair for self-promotion made him one of the most iconic artists of the 20th century.

Dali’s interests spanned a wide array of fields, from psychoanalysis and nuclear physics to optical illusions and religious history, all of which he intricately woven into his art. This broad vision and insatiable intellectual curiosity enabled him to create works that were not only visually striking but also deeply symbolic and profound.

His legacy lies in his ability to challenge and alter perceptions of reality, a skill that extended beyond the realm of art. Dali’s influence can be seen in popular culture and mass media, where his surrealistic vision has inspired countless movies, music videos, and advertising campaigns.