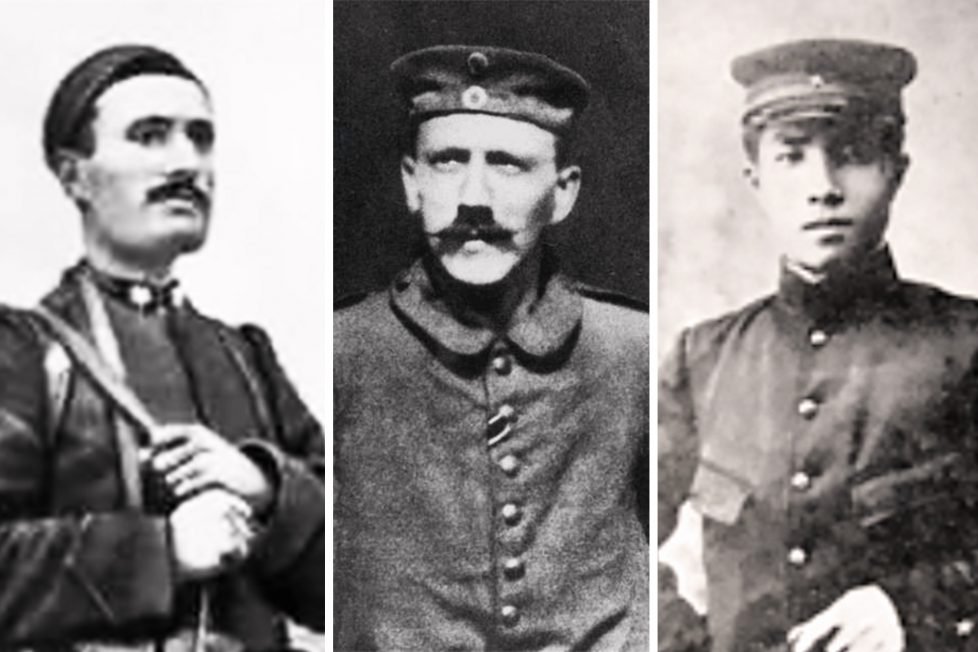

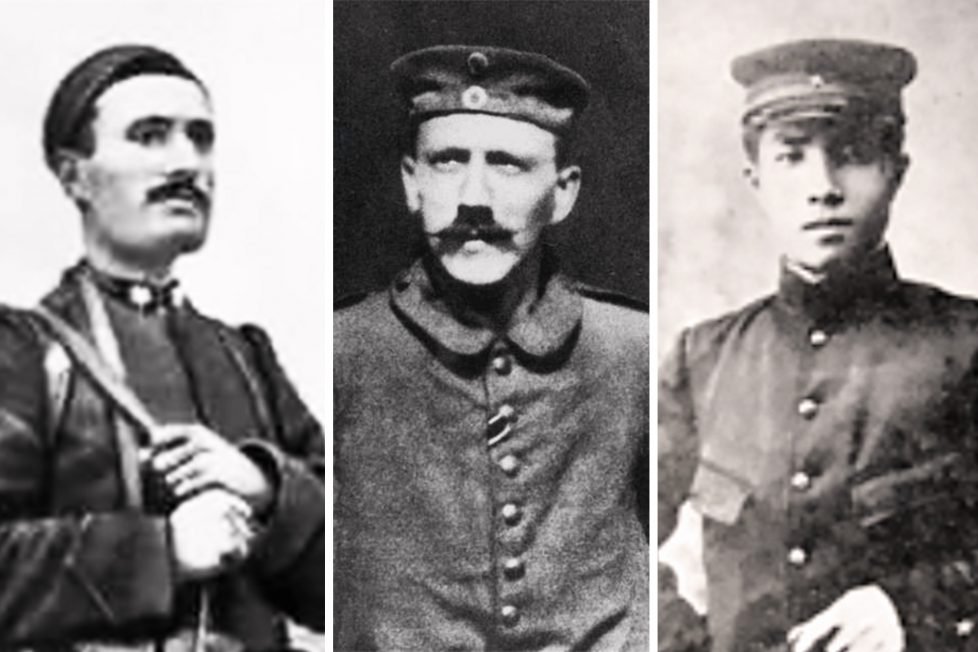

How Did WW1 Shape the Axis Leaders of WW2?

The formative World War I experiences that drove the ideologies and ambitions of Axis leaders in World War II

The formative World War I experiences that drove the ideologies and ambitions of Axis leaders in World War II

Table of Contents

ToggleMuch has been written about the leaders of the Second World War. However, something in common that many of the World War II leaders share is their experience in the First World War. Here we will take a look at how the period of the First World War shaped and affected the future leaders of the Axis nations.

Adolf Hitler, perhaps the most infamous individual in all of human history, was not actually German by birth. Rather he was born and raised in Austria, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1913, he moved from Vienna, Austria to Munich in Bavaria, Germany. In February 1914, Hitler would be called up for conscription in the Austro-Hungarian Army, which was universal for all Austro-Hungarian men. However, he would be determined, upon medical screening, to be unfit for military service.

However, when the First World War broke out in the summer of 1914, Hitler instead petitioned the King of Bavaria, Louis III, to allow him to volunteer for the Bavarian Army. A day later he would be given permission to join, although this was unlikely due to any sort of intervention by the King. Regardless, he would join up with the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment otherwise known as the List Regiment. After 8 weeks of training, he would be sent to the Western Front where he would spend the entirety of the War.

While at the Front, Hitler would be present for many of the Western Front’s most pivotal, and bloody, battles. Employed as a dispatch runner, he would be present at the First Battle of Ypres (1914) in Belgium. Later that year he would be awarded the Iron Cross, Second Class for his courage.

While being a dispatch runner was a dangerous assignment, requiring a soldier to deliver messages between units, it would also give Hitler reprieve from the constant combat on the front lines, with him spending a good deal of his time at the 16th’s headquarters at Fournes-en-Weppes. Here we see a sort of contradiction in that he was at once recognized as a courageous and conscientious soldier by his command, but was also considered an Etappenschwein or “rear-area pig” by many in his unit for the amount of time his assignment allowed him to stay safely in the rear areas.

Despite the comparative safety of his assignment, Hitler would still face the same dangers of the Front. At the Battle of the Somme (1916), he would be struck by artillery shrapnel in the left thigh. After his recovery, he would return to his unit in March of 1917, where he would be present at the Battles of Arras (1917) and Passchendaele (1917).

In the summer of 1918, he would receive both the Black Wound Badge and, upon the recommendation of the Jewish commanding officer Lieutenant Hugo Gutmann, he would also be awarded the Iron Cross, First Class. On October 15, 1918, Hitler was hit by mustard gas and lost his vision for a period of time. While recovering, he would learn of the signing of the Armistice that would end the war on November 11, 1918.

This came as a surprise for the wounded Hitler. Like many others, he did not believe that Germany was anywhere near losing the war. As a consequence, he soon bought into the Dolchstoßlegende or “stab in the back” myth that argued that it was the civilian leaders, the Jews, and Marxists that betrayed the still-fighting German Army. Later, he would refer to those who had signed the Armistice as the “November criminals.”

There is an intensive debate between historians on when Hitler truly embraced his murderous anti-semitism. Many argue that it was during his youth in Vienna, but others argue that it was Germany’s defeat in the First World War and his belief in the Dolchstoßlegende that led him down that road.

Regardless, the shock of Germany’s loss in the First World War would shape the future dictator. For Hitler, the war provided a purpose and convinced him of the virtue and usefulness of warfare. During his rise to political power, Hitler would often refer to himself as “the unknown corporal” to emphasize that he had come from the rank-in-file. What’s more, he would use his time in the First World War to emphasize the supposed betrayal of Germany’s leaders and, tragically, the supposed threat of the Jewish people.

Unlike Hitler, Benito Mussolini had already been heavily involved in Italian politics prior to the First World War. At the start of the War, he was the editor of the socialist newspaper Avanti! And was a rising star of Italian Socialist politics. At the outbreak of the war, the Italian Socialist Party advocated for a position of neutrality, while other European socialist parties had opted to back their respective countries’ entries into war.

While initially supporting Italy’s neutrality, Mussolini gradually began to see the war as a way for the revolutionary elements of Europe to sweep away the last empires of Europe i.e the Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and German Empires, which would lead to the possibilities of revolution at home and abroad. At the same time, he would begin to embrace nationalist sentiments in regard to the Italian population that lived under Austro-Hungarian rule. As a result, he began to argue that the war was a continuation of the Risorgimento or Italian Reunification.

These positions put him on the outs with Italian Socialist leadership, resulting in his expulsion from the party. He would leave his editor position at Avanti! and would, with funding from his wealthy mistress Margherita Sarfatti, the French government, and perhaps Russian agents, found the newspaper Il Popolo d’Italia (the People of Italy) which he would then use to promulgate his pro-interventionist ideas. While most Italians opposed entering the war, King Victor Emmanuel III forced the issue and Italy entered the First World War on the side of the Allies on May 24, 1915.

Mussolini was mobilized for service in August of that year. He would join the 33rd Battalion, 11th Bersaglieri Regiment, which was a regiment of sharpshooters that, along with their sister regiments, served with distinction on the Italian front. Mussolini would spend 17 months with his unit, although he received a great deal of leave for both health and political reasons. During this period he would be rejected from officer training, perhaps because of his political radicalism.

Despite what he would trumpet in Il Popolo d’Italia, and quite apart from Hitler, Mussolini disliked life in the army. He would manage to avoid fighting in Italy’s worst battles during the war (the Battles of Isonzo and the Trentino campaign) but nonetheless endured the terrible attritional warfare that so characterized the war. In his unpublished diary from that period, he conveyed an incredibly bleak outlook on Italy’s war, expressed deep regret for his interventionist stances, and noted his deteriorating health and morale.

Mussolini would ultimately be wounded in an accidental explosion in February of 1917. While he was only lightly wounded, he would remain in the hospital until August and took the rest of the war to fully recover. During this time he assumed full control over Il Popolo d’Italia, where he would continue to write pro-war propaganda.

Despite being on the winning side of the war, the Italians would receive, in their opinion, little in the way of territory, only getting Trieste, South Tyrol, Gorizia, and part of Istria. This produced the notion that Italy had won a “mutilated victory” that despite all the losses, suffering over 650,000 military dead and 950,000 wounded, they had been wronged by the Allies. All this was combined with a severe economic crisis that produced a turbulent situation in Italy.

Mussolini, abandoning socialism, believed that the situation was ripe for a revolution in Italy that would cross class lines. His time in the war imbued in him the notion that an “aristocracy of the trenches” could transform Italy. On 23 March 1919, Mussolini would officially establish the Italian Fascist movement.

The experience of Hideki Tojo (or Tojo Hideki following Japanese convention) during the First World War would be drastically different than that of both Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. While his European counterparts would experience firsthand the brutality of the War, Tojo would not see combat.

The son of a samurai turned army officer, Tojo would spend most of his life in the military climbing the ranks of command. In 1899, he joined the Japanese Military Academy, which graduated in 1905 and assumed the rank of Second Lieutenant. He would then go on to study at the Imperial War College which he would graduate from in 1915 with the rank of major. He would then be attached to the Kwantung Army in Manchuria.

While Imperial Japan had joined the Entente against the Central Powers in 1914, its role was small. And even within the Japanese military, only the Imperial Japanese Navy would play any major role. So while Hitler and Mussolini braved artillery, Tojo took up various administrative and regimental posts. Tojo would be sent to Siberia in 1918 as part of the abortive attempt by Entente to intervene in the Russian Civil War. This would effectively be Tojo’s only post where he would be involved in anything regarding the First World War.

What we see with Tojo’s time in the Japanese military during the First World War is a man working within and thriving in the military machine of Imperial Japan. He would later be called “the Razor” for his bureaucratic efficiency. Like many of his fellow officers, Tojo held nationalist views that pushed for Japan’s expansion.

While he saw no combat in the First World War, Tojo spent these years rising through the ranks of the Imperial Japanese Military. The First World War shaped Tojo indirectly insomuch as he was part of and rising through the ranks of an aggressive, expansionist, and increasingly nationalist Japan. Unlike the millions of casualties that both Germany and Italy suffered in the war, Japan had suffered a mere 415 dead. The war proved to be nothing but a boon for Japan, and by extension, Tojo.

The experiences of these three future Axis leaders during the First World War were not only formative but also reflective of the sentiments in their respective nations. Hitler, impacted by the horrors of the Western Front, felt betrayed by the Weimar Republic and aimed to dismantle it. Mussolini, despite fighting on the front lines, felt that Italy’s victory was not fully honored, fueling his desire for a new Roman Empire. Meanwhile, Hideki Tojo advanced through the ranks of Japan’s military during a time of growing imperialism, a trend he would continue as a leader. Both Hitler and Mussolini aimed to overthrow the political systems they felt had betrayed them, while Tojo sought to expand upon the very system that had enabled his rise. Their leadership in the Second World War can, in large part, be attributed to their respective experiences in the First.