The History of Abstract Expressionism

A movement that purposefully has no subject matter.

A movement that purposefully has no subject matter.

Table of Contents

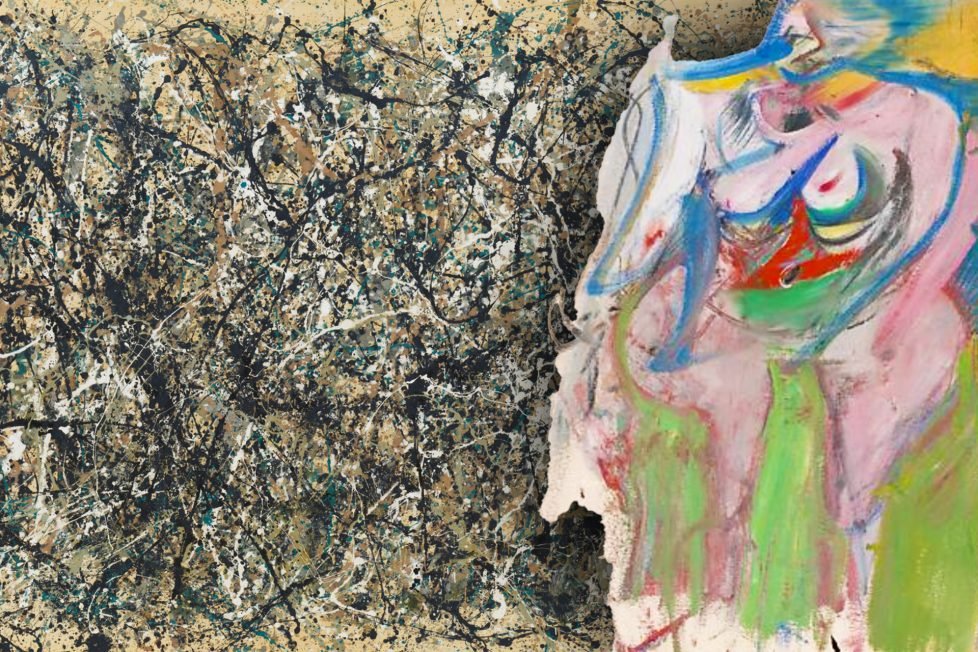

ToggleWhen experiencing modern art, many of us have excitedly thought, “I can do that!” or a defeated “I don’t get it.” Indeed, Jackson Pollock’s (1912-1956) One: Number 31, 1950 (1950) seems as if someone let loose a toddler upon the canvas flinging paint without any care or thought. What’s left is a tangled mess of paint splatter that does not seem to have any clear subject matter. What are we supposed to make of it? Are we supposed to make something of it? Abstraction, the reduction of the lifelike to its simplest forms, would say no, which is the point.

The concept of abstraction in art can be traced back to the end of the 19th century, well before the emergence of Abstract Expressionism. However, when the movement emerged in the United States between the 1940s and 1950s as a reaction to World War II, it was the first time complete abstraction took place in art. The first generation of these artists, officially referred to as the Abstract Expressionists in 1946, promoted the radical shift from figurative art to complete abstraction. Gone were the easy-to-read paintings with their obvious subject matter in favor of the basics of painting: line, color, form. What caused such a drastic shift?

It was the art critic Clement Greenberg who, in his essay “American-Type’ Painting” (1955), explained the appeal of Abstract Expressionism to the skeptical public. Much like many of us today, society then did not understand what to make of abstract art. They were used to history paintings like Benjamin West’s (1738-1820) Helen Brought to Paris (1776), which showed the Greek myth surrounding Paris and Helen’s love story that sparked the Trojan War. Such subject matter was well-known, allowing anyone to understand the basics of the painting. Even the work of the post-Impressionists, who first began embracing abstraction, still had clear subject matter even if it was no longer realistic. Abstract Expressionism and its complete expulsion of subject matter went against art’s most accepted tradition.

According to Greenberg, these painters were following the legacy of art history. He believed modern art was not a break from tradition as many saw it. Instead, Abstract Expressionism was a part of the natural progression of Western visual arts. At this point in artmaking, Greenberg believed artists should emphasize what made each medium unique. For painting, this meant realistic subject matter was no longer the goal. Instead, artists should want to emphasize the painting’s flat plane, what Greenberg called its “medium specificity.” Since painting is a two-dimensional medium, there could not be any sense of three-dimensional space as that was the medium specificity of sculpture.

From the pioneer group of Abstract Expressionists came two strains of abstract artmaking. First, there was the action, or gestural, painters most often represented by Pollock. Then there were those, like Mark Rothko (1903-1970), who were considered color field painters. While both groups approached abstraction differently, they embraced flatness with huge, unstretched canvases and no subject matter.

Art critic Harold Rosenberg coined the term “action painting” in 1952. According to Rosenberg, the artist’s active use of paint on the canvas defined this type of abstraction. Such abstraction was about an artist’s encounter with the canvas as it reflected a record of an artist’s action. As Rosenberg believed, this action showed their unconsciousness because of their improvised gestures. This interest in the unconscious stemmed from Surrealism, an art movement that rejected typical art conventions a few decades before Abstract Expressionism emerged.

The most common example of action painting would be Pollock’s drip paintings, such as Number 1A, 1948. Pollock would lay the canvas on the floor so that he could fling or drip globs of paint onto it. This action created a tangled web of paint splatter that Pollock that was not pre-planned, which led Rosenberg to believe that action painting showed an artist’s unconscious. In addition, he argued such work showed an artist’s individuality as he related Pollock’s drips to a traditional artist’s mark.

The other strain of Abstract Expressionism, the one Greenberg coined, focused on painting huge blocks of color across enormous canvases. The most well-known of this group was Mark Rothko (1903-1970) and his work, such as No. 16 (1960). This work shows a blue canvas with three distinct sections painted red, green, and brown. These rectangular sections do not touch and are unequal in size. Such large regions of color are why these artists got their name “color field.”

Unlike the action painters, the color field painters planned their paintings. Rather than get a sense of an artist’s psyche, color field painters wanted to express human emotion by enveloping the viewer with large blocks of color. In this way, color field painting was more about shared universal experiences rather than the artist’s individuality.

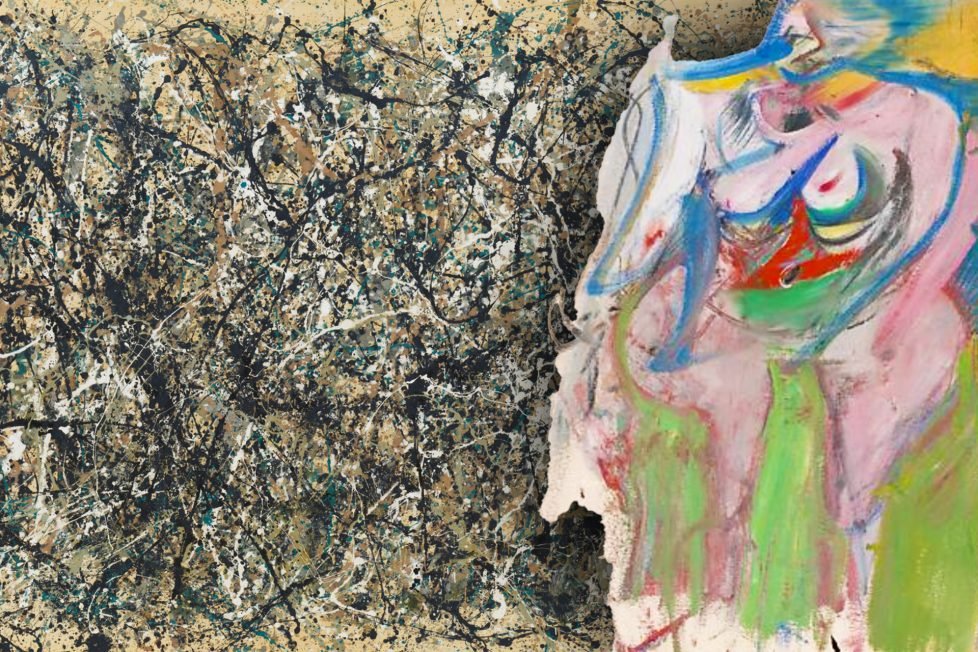

Other well-known members of the early Abstract Expressionists were Willem de Kooning (1904-1997) and Barnett Newman (1905-1970). While de Kooning was an action painter, Newman was a color field painter. When looking at an example of each of their art, we can see the problem with Abstract Expressionism. That is, the movement was male-dominated and, by extension, centered on a male viewpoint. This viewpoint would further the “artist genius” myth, understood as strictly male, and was a point of contention for the female Abstract Expressionists.

Looking at de Kooning’s Two Women (1953) aligns with the movement’s goal. We see the flatness of the canvas emphasized as there is no clear distinction between the foreground and background. In addition, there are large swaths of color and harsh lines that do not give a sense of clear subject matter. Indeed, the title is what clues us into how this piece might contain two female figures. De Kooning’s use of the art convention of the female nude relegates these figures to their bodies. Notably, de Kooning emphasized their breasts and childbearing hips while refusing to paint their faces. While this would align with the movement’s goal to not have a realistic portrayal, de Kooning did not even paint a semblance of these figures’ heads. Instead, they appear like headless mannequins, all for the male gaze.

Meanwhile, Newman follows the color field painters. His Vir Heroicus Sublimis (1950-1951) engulfs the viewer’s eyesight with a seven-foot by seventeen-foot red canvas, only broken by five vertical strips of color. Two aspects are of note. First, Newman’s Latin title means “Man, heroic and sublime.” Two, red is a color most associated with anger or passion. Newman’s color, size, and title reflect the hypermasculinity of the time that came about because of World War II. Newman reflects men’s desire to stick to their gender roles by emphasizing their size, strength, and passion.

The work of Louise Fishman (1939-2021) pointedly objects to the male-dominated and male-centered viewpoint of Abstract Expressionism. Her 1973 “Angry Women” series is the best example. Two paintings, Angry Louise (1973) and Angry Marilyn (1973), show that Fishman dedicated this series to herself and other women she may or may not have known, like Marilyn Monroe. Both paintings appear similar in their composition. Fishman struck the canvas with slashes of paint, charcoal, and pencil with bold colors and harsh lines. Likewise, Fishman writes in all capital letters before her name and Marilyn’s, “ANGRY.” Fishman emphasized this emotion more on her own canvas when she added, “SERIOUS RAGE.”

As both a feminist and queer artist, Fishman contested the idea that rage is unfeminine and that women must cater to the male gaze. Her art, with its muddied color and harsh lines, is not what we would consider beautiful but does express womanhood in a real and raw way. Doing so shows a shift away from focusing on the artist or expressing a vague idea of emotion to a more pointed universal experience that Fishman and other women could relate to. In this way, abstraction becomes invested with the political.

Indeed, the movement was seen as apolitical. As the post-war years continued and social movements began forming, artists did not like Abstract Expressionism’s complete expulsion of subject matter. As a reaction against it, Neo-Dada emerged. After Dada (a reaction to World War I), Abstract Expressionism was the art world shifting from overtly anti-war to abstract apolitical art. The Neo-Dadaists emerged around the 1950s and 1960s to bring back politics in art as well as subject matter.

One such artist, Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008), shows how artists became disillusioned with the beliefs of Abstract Expressionism. An example is his Bed (1955), which hangs on the wall but is not flat like a painting. This goes against the idea of focusing on the flatness of painting and even goes so far as to combine the medium with sculpture, as Bed has three-dimensional components. Additionally, Rauschenberg mimics Pollock’s drip with splatters of paint dripping down the pillow and onto the quilt. Such a move contests the individuality of Pollock’s mark since Rauschenberg could replicate it.

As other Neo-Dadaists made similar works, Abstract Expressionism began to fall by the wayside. However, the idea of abstraction would stick around and lead to other movements, such as Minimalism and Pop Art. Whether we “get” it or not, the emergence of complete abstraction was a defining moment in art history and placed New York City on the map of the art world.