Pre-Columbian Era: Mexico Before European Contact

From the Anahuac Valley to the Sonoran Desert, Mexico was a vastly different place before European contact

From the Anahuac Valley to the Sonoran Desert, Mexico was a vastly different place before European contact

Table of Contents

ToggleBefore European explorers ever made contact with the New World in the 15th century, the Americas was a vastly different continent. Thriving civilizations and diverse cultures could be found throughout most of the Americas, with Mesoamerica being an important blossoming epicenter.

From the Olmecs and their colossal head sculptures, to the Aztecs and their sun stone, the territory now known as Mexico and Central America saw fascinating cultures and great feats of humanity. Yet the story of said cultures begins thousands of years earlier, with the prehistory in the Americas and the archaic era. Later, the preclassic period, sometimes called the formative era, saw the beginning of some of the first agricultural cultures. By the classic and postclassic eras, these civilizations had developed further, achieving great complexity.

Beginning around 16,500 BCE, groups of hunter-gatherers migrated into the Americas and started populating the continent. The traditional theory argues that Paleolithic humans entered the Americas through the Bering land-bridge which had formed during the Last Glacial Maximum in the Last Ice Age. Other theories suggest different routes or earlier timelines, yet they all remain broadly still unconfirmed.

Regardless, the Paleo-Indians, the first peoples to inhabit the Americas, spread throughout much of the continent and reached a variety of places which would lead to a diverse flourishing of cultures. For much of the American continents’ prehistory, humans developed mainly nomadic lifestyles with ample use of stone tools. The Clovis culture was a hunter-gatherer culture based around big game hunting in North America. It was, for a long time, considered to be the first culture to have developed from the Paleo-Indians, yet it is now believed that other pre-Clovis cultures developed throughout North America.

The Folsom tradition, a similar Paleo-Indian culture derived from the Clovis culture, spread through most of central North America, from the north of Mexico, through the middle of the United States and up to the south of Canada. After the Folsom tradition, the Americas reached the Archaic era where cultures such as the Archaic Southwest in North America and the Chan-Chan culture in South America began depending more on intensive gathering practices and less on big game hunting. The megafauna population had declined in the early stages of this period, and food production by means of agriculture started to take place.

Also known as the Formative stage, the Preclassic period (2000 BCE to 250 CE) saw the birth and development of regional cultures with sedentary lifestyles based on more modest forms of agriculture. In the North American Arctic, the Dorset culture appeared. In central Mexico, the Olmecs and Zapotecs developed, the first occupied the tropical lowlands of Veracruz and Tabasco, next to the Gulf of Mexico, and the latter spread in the Valley of Oaxaca. In North America, the Woodland and Mississippian cultures developed mostly in the southeast of the United States.

The Olmecs were the first major Mesoamerican culture. Known to the Aztecs as the “rubber people” for their extraction of latex from a regional rubber tree, the Olmecs were the first at many of the things that other cultures would later adopt. Though preceding the Aztecs for thousands of years, the Olmecs played the Mesoamerican ballgame and practiced the ritual of bloodletting, for example. Their art and artifacts are considered among the most beautiful and enigmatic. The famous colossal heads, for example, are fascinating for what they appear to be — representing rulers and rulership and sculpted from basalt yet perhaps originally painted and with facial features resembling those of African populations.

To the south of the Olmecs, the Zapotecs started as a sedentary culture with agricultural settlements. They too shared similar characteristics with the Olmecs, like their production of jewelry and ceramics. Also, a shared feature, both the Olmecs and Zapotecs already showed beliefs associated with a rain deity and a feathered-serpent deity, which were largely shared by many cultures in Mesoamerica. To the east, the Mayans began developing their first civilization in the Yucatan peninsula. Though less advanced than the Olmecs or Zapotecs, the Mayans spread and built cities which eventually were abandoned, yet their first collapse would not be their last and they eventually grew into a majestic civilization that outlived the Olmecs.

So far, we have seen the beginnings of human cultures in the Americas and the development of the first civilizations in Mesoamerica. Yet, to better understand pre-Columbian Mexico, it is necessary to understand what exactly Mesoamerica is and what it means for the history of the Americas. Unlike the term, Middle America, a synonym to Central America (Centroamerica in Spanish), Mesoamerica does not refer to the central region in the Americas. Its location on the continent is similar to that of Middle America and its name is of similar meaning, yet Mesoamerica refers to a historical cultural area and not a geographical one. Coined by German anthropologist Paul Kirchhoff, the term “Mesoamerica” refers to the cultural area encompassing central and southern Mexico and the neighboring parts of Central America.

For Kirchhoff, Mesoamerica comprised a specific cultural area given the shared features among the cultures that inhabited it. A sedentary lifestyle, advanced agricultural methods and practices, such as the milpa system, a pictographic writing system and other already mentioned features like the ballgame, made Mesoamerican cultures closer to each other than to other indigenous cultures in the continent like those in North and South America. The limits of Mesoamerica, however, are not fixed and can be better understood as an “unstable frontier”, at least when it comes to its northern border. Other cultures existed outside Mesoamerica, yet they were different and largely separate. Kirchhoff defined these other regions as Aridoamerica and Oasisamerica. The different regions are not to be understood as completely different places with no connection between them. Instead, the regions can be appreciated as similar places defined by their specific environments yet with shared features and clear links.

Aridoamerica saw isolated and compact cultures that were defined by their environment, thus the name. The region spanned the north of Mexico and parts of the southern United States. The climate conditions made it extremely difficult for cultures to develop sedentary lifestyles based on agriculture. Instead, cultures in Aridoamerica were hunter-gatherers in mostly constant movement. Some of the cultures that developed in Aridoamerica were the Mayo people, the Yaqui people, and the Pericu people. Many, like the Mayo and Yaqui, continue to live as descendant cultures today. In Oasisamerica, people migrated away from the desert to lands closer to bodies of water with less harsher climates. They lived sedentary lifestyles, but the inefficient forms of agriculture were complimented by hunting and gathering practices.

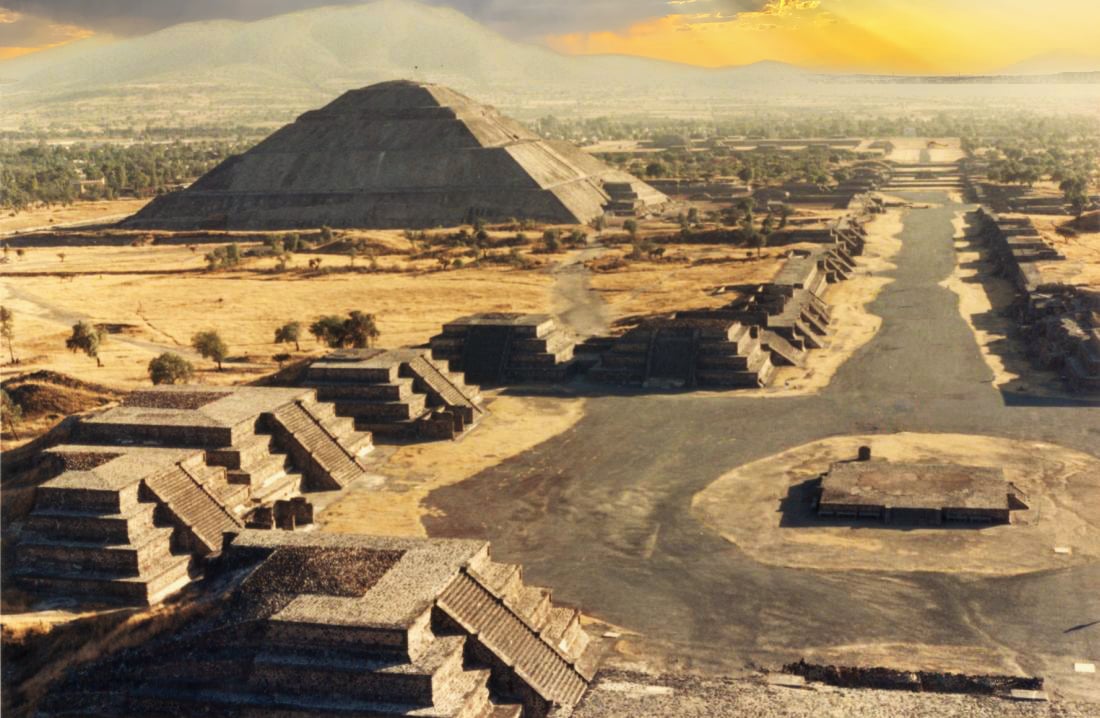

After the preclassic period, major civilizations arose in Mesoamerica, reaching important milestones in the history of the Americas. The biggest and most famous was the city-state of Teotihuacan. The history of Teotihuacan is often intertwined with mythology, given the importance that the city had on Mesoamerica as a whole. The Aztecs believed the universe was founded in Teotihuacan and that the Gods came from there. Still, Teotihuacan was a majestic city regardless of the mythology. Culture thrived in Teotihuacan and influenced even the Mayans with their constant, often violent, exchanges.

Teotihuacan reached its zenith around the years 200 to 600 CE, when it was the largest and most populated settlement in the Americas and likely one of the largest in the world too. Teotihuacan’s influence reached the Zapotecs and the Mayans, but it inspired following cultures as well, with the Toltecs and Aztecs traveling to Teotihuacan to understand its fall. The Toltecs likely played a part in the collapse of Teotihuacan, given their coinciding growth with the decadence of Teotihuacan. The majestic pyramid of the sun is one of the most emblematic elements of pre-Columbian heritage.

In the southeast, the Maya civilization reached new heights: the classic Mayans erected monuments, built large-scale constructions, had an advanced understanding of urbanism, intellectual and artistic flourishing. The Mayans of the classic period are often likened to other classical civilizations such as the Greeks, given their complex nature of society with alliances between city-states and conflicts among themselves. The Mayans were in close contact with Teotihuacan, with constant intervention from the latter. The Mayans of the classical period eventually suffered a major collapse. Subject to misunderstanding and oftentimes conspiracy theories, the classic Maya collapse was very likely due to complex and harsh dynamics in the region, such as conflict and drought.

The Postclassic (950 CE to 1521) was the final era of pre-Columbian Mexico. Marked by the rise and consolidation of the Aztec Empire, the era is broadly the best-known period of pre-Columbian history in Mexico. Incorrectly known as the Aztecs, the Mexica people founded the city of Tenochtitlan and formed the second largest pre-Columbian empire in the Americas after the Inca people. The term “Aztec” refers to the mythical origin of the Mexica, suggesting they journeyed to central Mexico from their legendary northern homeland, Aztlan. Once in the Valley of Mexico, however, the Aztecs became known as the Mexica people. The Nahua people, another prominent group, had migrated from the north into the central region, with the Toltecs being a major Nahua civilization.

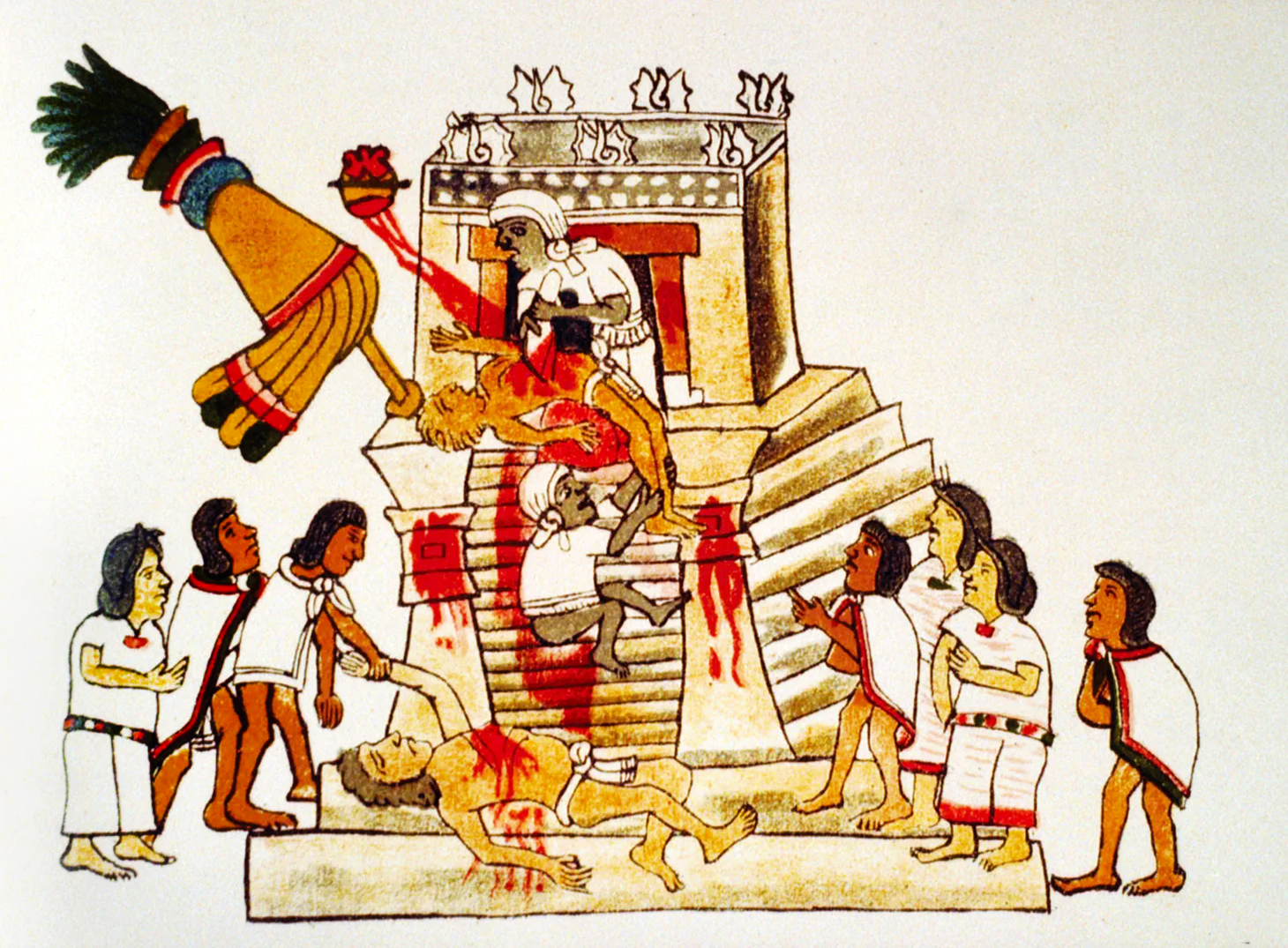

The Mexica people arrived in central Mexico and formed small city-states. They eventually settled at the Lake of Texcoco, after being banished from nearby lands. Most of the good land had already been taken and rival city-states were hostile to the Mexica, who were known as formidable fighters. The Mexica allied with Azcapotzalco but eventually turned against them with the formation of the Triple Alliance alongside the city-states of Texcoco and Tlacopan. The Mexica soon rose into dominance thanks to their ruthlessness and militaristic focus. Instead of killing most of their enemies, the Mexica captured them for ritual purposes. The fighting mentality was ingrained into their belief system. The war god Huitzilopochtli, for example, was a guiding force in Mexica warfare.

The Mexica civilization ended a few decades after the arrival of Cristopher Columbus, with the Spanish conquest of Mesoamerica and the fall of the Aztec Empire. Other postclassic civilizations were able to resist the Spanish conquest, but only for a while. To the west of Tenochtitlan, the Purepecha Empire was a mighty civilization that was able to not only resist the Mexica’s attacks and attempts for conquest, but also fought against the Spanish. Their initial attempts of becoming subjects to avoid the bloodshed, failed, resulting in conflict.

Remarkably, for more than a century, a few Mayan kingdoms, such as the Yayasal and the Kowoj remained unconquered by the Spanish.