Fatima Al-Fihri: Founder of the World’s Oldest University

In the 9th century, Fatima Al-Fihri founded a center of learning and worship. Her legacy lives on to this day.

In the 9th century, Fatima Al-Fihri founded a center of learning and worship. Her legacy lives on to this day.

Table of Contents

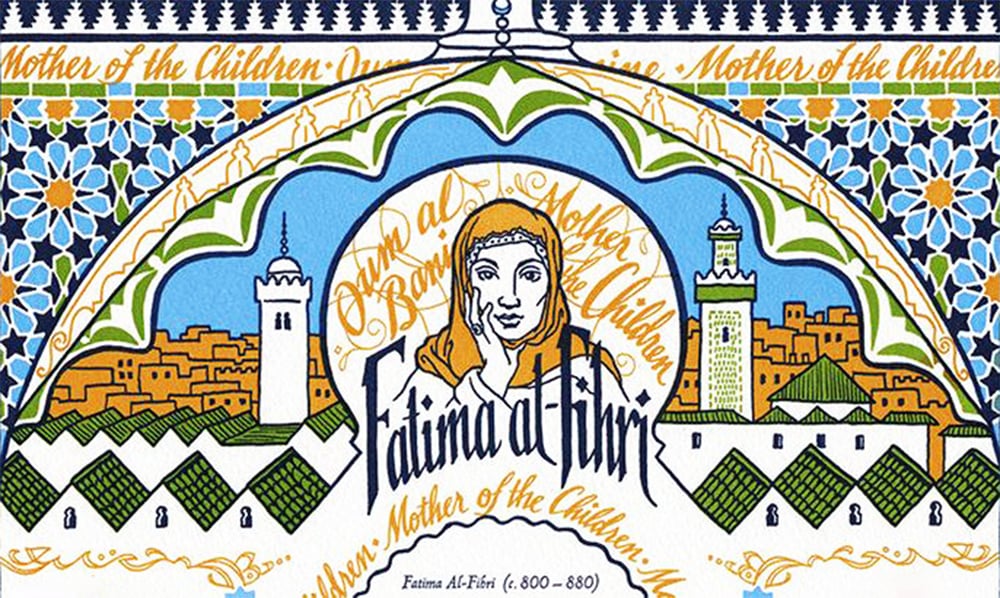

ToggleFatima Al-Fihri may not be a household name, but her impact on the world is resounding. Not only the Al-Qarawiyyin mosque, university and library she founded in the 9th century are still in operation, and are considered symbols of the culture and history of Fes (Morocco), but her legacy as a champion of education helped create one of the preeminent centers of learning in the Islamic Golden Age.

Al-Qarawiyyin is located in the north west of Fes, in the ‘Fes-el-Bali’, the ancient heart of the city. At its height in the 13th and 14th century, Al-Qarawiyyin boasted hundreds of students – so many that dozens of madrassas (religious schools) were commissioned in the surrounding suburbs to house students from Al-Qarawiyyin. The library at this time consisted of over 30,000 volumes from across the Islamic World and Europe.

According to UNESCO and the Guinness World Records, Al-Qarawiyyin is the oldest continually-run, and the first degree-granting university in the world, although it was only in 1963 that it became a state university. While some say this title should go to the University of Bologna (established in 1088) because Al-Qarawiyyin didn’t self-describe as a university until much later after it was founded, others counter that the University of Bologna was modeled after Al-Qarawiyyin!

Whichever way you look at it, the quibble over titles doesn’t diminish the illustrious history of the place, or the fact that students of Fatima’s Al-Qarawiyyin became some of the most distinguished minds in history.

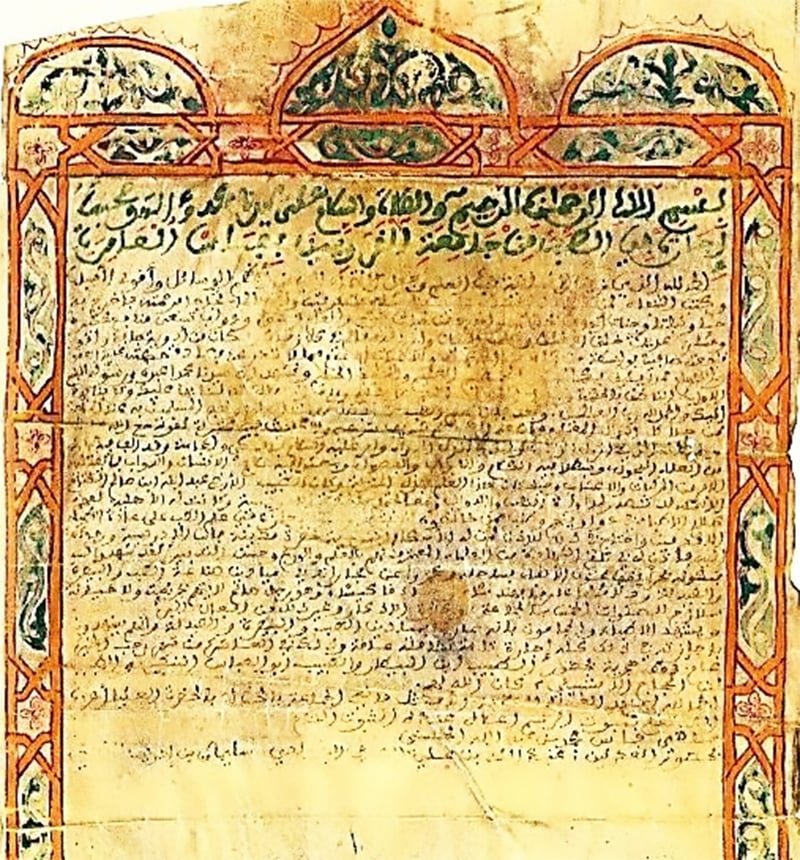

In 1323, a fire ravaged the Al-Qarawiyyin library and destroyed most of the thousands of manuscripts held there, including many primary sources and other documents detailing Fatima Al-Fihri’s life. Luckily for us, shortly after the fire a local scholar, Ibn Abi Zar, wrote a detailed history of the city of Fes, and included many details about the life and contribution of Fatima Al-Fihri.

She was born in 800 CE to a merchant family in Qayrawan (present day Karaouine), Tunisia, amid the turmoil of power struggles between the Berber tribes and the ruling Caliphate in Baghdad. That same year, the Caliph granted its victorious agent, Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab, the title of Emir in Qayrawan, giving him hereditary ruling rights of an almost-independent state across the region, where he then established the Aghlabid Dynasty.

This was not great news for Fatima’s family, as they belonged to a persecuted group of Shias. After an unsuccessful rebellion against the Aghlabids in 824 CE, Fatima’s family, along with 2,000 other Shia families, were banished from the city. They traveled to Fes with most of the other exiles and settled there. As a city of migrants, Fes was the perfect place for business to flourish, and Fatima’s father re-established himself as a wealthy and respected merchant in the city.

While we don’t know many details of Fatima’s early life and time in Fes, we do know that her father was passionate about her and her sister Mariam’s education. Growing up, they were tutored at home, as was the custom of the time for middle and upper-class women. Fatimah married and lived according to the standards of a devout woman, tending her household and spending her time in study and charitable pursuits. Life changed drastically for her when her husband, brother and father died within a short time of one another. Fatima would have been in her fifties at the time.

Fatima and Mariam were left a sizable inheritance by their father. Both women were determined to see this inheritance turned into a lasting legacy. Mariam used her newfound wealth to establish a mosque in the Andalusian quarter on Fes, naming it ‘Al-Andalus’ after the migrants who had settled that district – the mosque is still in operation. In similar fashion (and located quite close by), Fatima also established a mosque, naming it after her hometown of Qayrawan. She couldn’t have known it at the time, but this was the birth of the world’s oldest continually run university and a legacy much larger than Fatima could have envisaged.

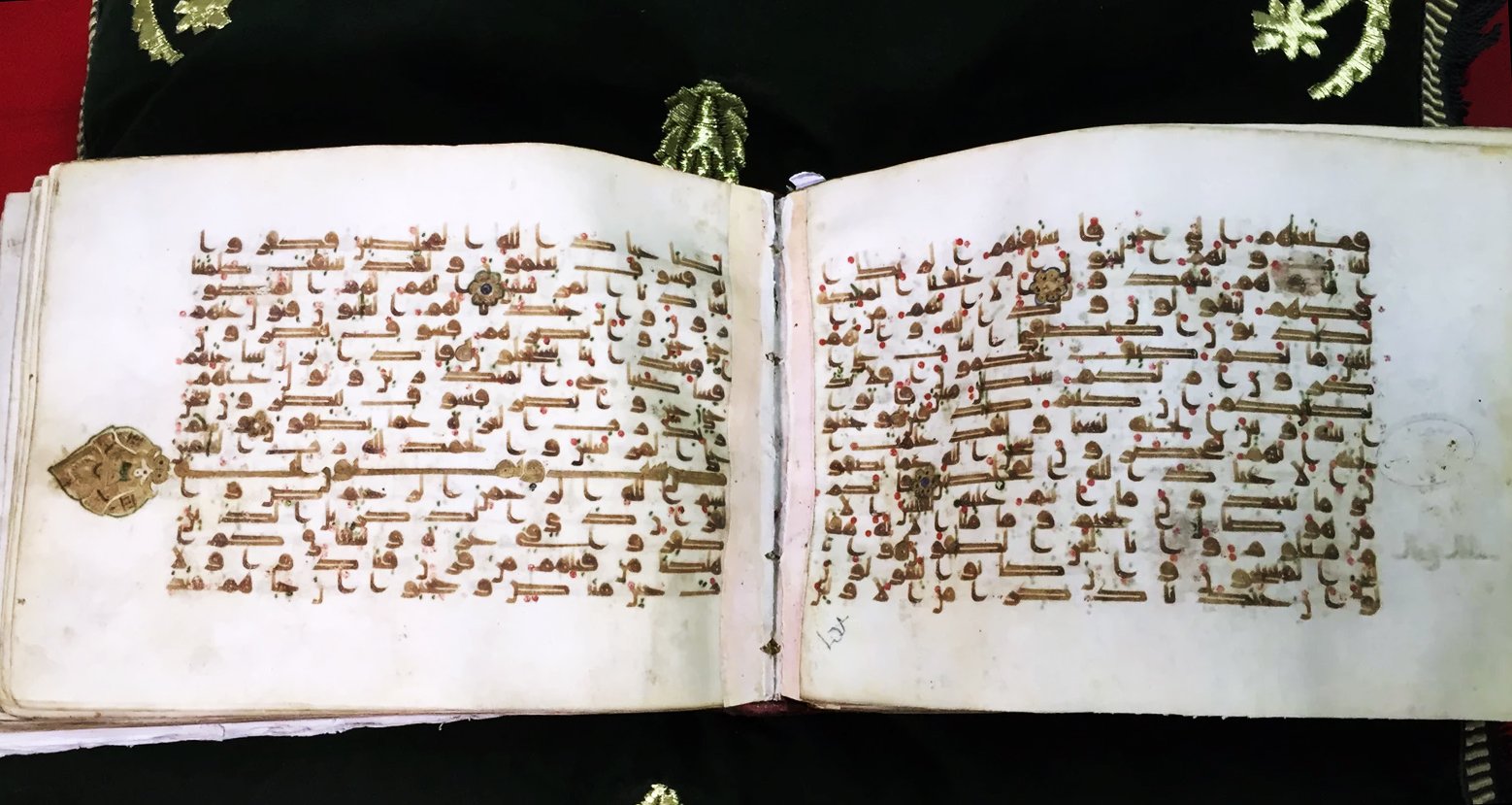

The initial mosque and madrassa (or school) of Al-Qarawiyyin was completed in 859 CE. The library was completed the same year and remains one of the oldest in continual use, claiming a similar title to the university itself. The library’s restoration, carried out by female architect Aziza Chaouni in 2016, secured more than 4,000 ancient manuscripts, (including the oldest known medical degree from the 12th century), and is one of the reasons Fatima’s story has gained more traction in the mainstream.

Fatima remained at the head of Al-Qarawiyyin until her death in 880 CE. She played a central role in establishing Al-Qarawiyyin not just as a place of worship but as a center of higher learning. She became known as the ‘Mother of Boys’ for her habit of taking students under her wing and supporting their studies financially and with her own considerable knowledge – being a respected scholar of Hadith (lessons and sayings of the Prophet Muhammad) and jurisprudence.

While there is little known about the earliest days of the mosque and madrassa, it did not take long for Al-Qarawiyyin to become renowned as a seat of learning. The syllabus was expanded beyond the Qur’an and Islamic theological studies to include a range of science and philosophy subjects. People who could read the Qur’an and had learned the Hadith and jurisprudence – as Fatima herself did – were considered highly educated. By expanding the field of learning further, Al-Qarawiyyin cemented itself as a beacon for those seeking advanced knowledge. The University became a light that shone brightly during the Islamic Golden Age.

Many modern readers of Fatima’s life and legacy hold her up as an empowered woman (she certainly was that) breaking barriers to female participation in society. But was Fatima really breaking barriers by partaking in the academic and religious life of Al-Qarawiyyin?

For a 9th century woman, it would have been perfectly acceptable, with no father, husband or brother as protector, to retire to a quiet life at home, but Fatima chose to dedicate her time and fortune to learning. Yes, a public life was not overly common for women of her day, but as an educated woman of independent means, it wasn’t so out of the ordinary, either. Certainly, far from prohibited.

In fact, many women were well educated in Fatima’s day and were highly valued and respected in society. Women were often the patrons of mosques and charitable institutions, some even held government positions. There is also a long tradition of Muslim female scholarship beginning with the advent of Islam in the 7th Century. If we’re looking from the viewpoint of Fatima, the barriers she would have been more intent on breaking were monetary ones; income was a bigger obstacle to education than gender, and this is where much of her charitable efforts were focused.

Fatima probably would not have considered her activities trailblazing. However, her story is often viewed through the lens of the history (and biases) that came after her, which is why she is so often heralded as a symbol of female empowerment.

As Al-Qarawiyyin became more renowned, places at the university became sought-after, so much so that they began setting entrance conditions. For example, it became mandatory that a Muslim student had already memorized the Qur’an prior to taking their place at the University. Of course, the madrassa still operated as a place to learn the Qur’an before gaining entry to the University proper.

As a center of intellectual exchange, the University attracted scholars and students from across the Islamic world and beyond. Al-Qarawiyyin provided a comprehensive education in various fields of study, including theology, law, grammar, medicine, mathematics, and more. Students who maintained regular attendance at the University over a period of five years, and demonstrated mastery of a subject matter were granted an ‘Ijazah’ or license, in that subject – a system which paved the way for the modern concept of awarding degrees.

By the mid 900’s Al-Qarawiyyin was given the honor of being designated the official Friday Mosque of Fes. Shortly afterwards, the buildings were enlarged through a sizable donation from the ruling Amirids, and later significant renovations were carried out by the Almoravids in the 12th century. Thanks to Fatima’s foresight, the surrounding land had been purchased at the time of the initial construction of the Mosque, making extension projects easy to complete.

The university attracted intellectuals from across the Islamic world and Europe, which fostered the continuation of knowledge and sowed the seeds for the flourishing of the Renaissance.

Notable alumni of Al-Qarawiyyin include:

Fatima Al-Fihri is not a very well-known figure in the West, however her legacy is far-reaching. Her dedication to the advancement of knowledge helped to shape one of the most prolonged eras of human understanding, and sowed seeds that would germinate in the most unlikely of places – from laying the foundation for the system of degree-granting universities we know today, to influencing the graduate dress of modern universities down to the mortar board hat (a symbol of the supremacy of scripture over intellect left over from the Golden Age of Islam).

As a female role model in Islamic history, Fatima is admired by many, although her legend may have become stretched over the centuries:

Some stories claim Fatima was actually a Tunisian Princess fleeing the barbarous invaders of Karaouine who had less-than-honorable intentions towards her. Local legends say Fatima fasted the 18 years it took to build Al-Qarawiyyin (more likely she just fasted regularly, as was common practice). Fatima is even considered by some to be an Islamic Saint, or Walia. While it’s not possible to confirm this claim, her focus on spreading knowledge – dedicating her life and fortune to the cause – is inspiring enough.

Fatima Al-Fihri’s contribution to the blossoming of the Islamic Golden Age is undeniable. Al-Qarawiyyin was a preeminent center of learning in the world at the time, and continues in its rich traditions to this day.

Since the restoration of the Al-Qarawiyyin Library in 2016, the legend of Fatima Al-Fihri has gained more traction in the mainstream. She was an exceptionally dedicated woman, but perhaps not the kind of exception for her time that our modern viewpoint may wish to paint her. She stands on the shoulders of a rich tradition of Muslim female scholars and patronesses, and used her light to shine the way for many more to follow her afterwards.