Grant Wood’s Paintings: American Gothic and 22 Others

Explore hidden narratives and vibrant aesthetics in Grant Wood's lesser-known paintings.

Explore hidden narratives and vibrant aesthetics in Grant Wood's lesser-known paintings.

Table of Contents

ToggleGrant Wood is a name that resonates in the annals of American art history, predominantly due to his emblematic 1930 masterpiece “American Gothic”. This evocative image of a stern-faced farmer standing alongside a woman against the backdrop of a Gothic-style farmhouse has become one of the most recognized pieces of twentieth-century American art. However, the broad, diverse body of work that Wood produced in his career extends far beyond this iconic piece. This article aims to unveil and explore the depth and richness of 22 lesser-known yet equally captivating works by this great artist.

Born in 1891 near Anamosa, Iowa, Grant Wood spent the majority of his life in the American Midwest, the landscape and people of which had a profound influence on his work. After spending time in Europe and briefly adopting an impressionistic style, Wood returned to his roots both geographically and stylistically. He became one of the leading figures of the American Regionalist movement, a style that celebrated rural life and was steeped in a deeply American sensibility. His works, often characterized by their meticulous detail and a sense of solidity and permanence, resonate with an intimate understanding of his subjects, derived from a lifetime spent observing the rhythms of life in the rural Midwest.

In the following exploration, we’ll traverse the breadth of Wood’s creative journey, diving deep into his evocative landscapes, portraits, and scenes of rural life that never garnered as much fame as ‘American Gothic’ but are equally compelling.

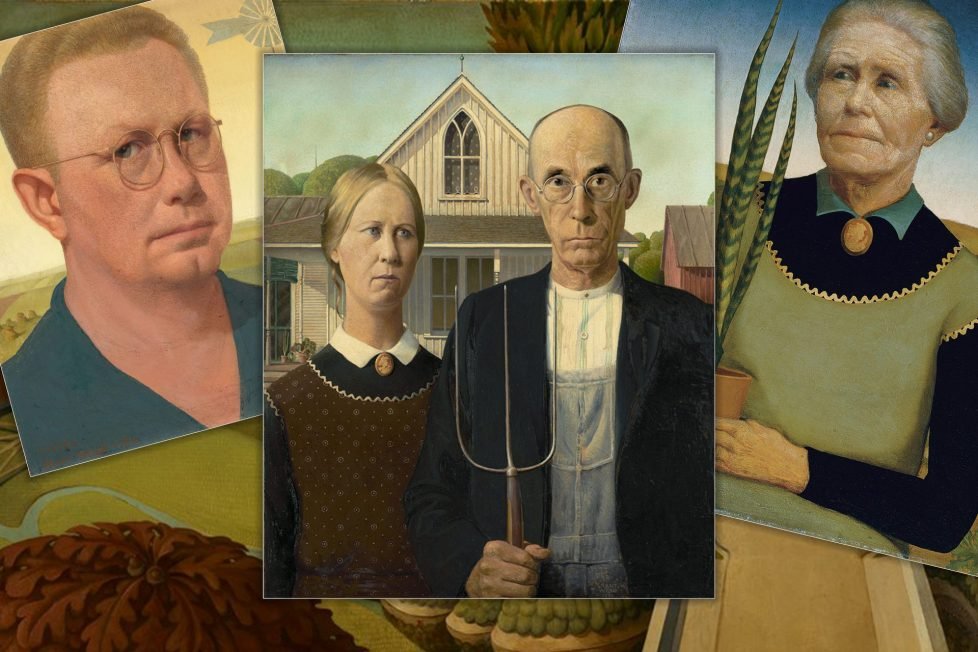

Grant Wood painted “Woman with Plants” in 1929. Just a year shy of his masterpiece, “American Gothic”. This piece features a half-length portrait of his mother, the steely and resolute Hattie Weaver Wood.

“Woman with Plants” is compelling in its simplicity. Wood places his subject front and center. Hattie dominates the canvas with her calm resilience. Commanding the scene alongside her is a snake plant. Hattie grips it tightly, its sharp leaves piercing the air like warrior’s swords. The plant’s details unravel the deep bond she shares with it, representing her personality — determined and unfaltering.

The synergy between the woman and the plant is uncanny. They mirror each other’s strength, forming a unified symbol of endurance emblematic of Wood’s works.

Ultimately, “Woman with Plants” is a loving tribute to Wood’s mother. Her strength, tenacity, and undying link to nature are beautifully captured. It signals the artist’s eternal respect, honoring the unwavering spirit that gave him life and paving the way for the ethos that would define his art.

“Arnold Comes of Age” certainly stirs a tale. Painted by Wood in 1930, this picture was originally a birthday gift for his young assistant, Arnold Pyle. Wood was known for his deep affection towards Pyle, whom he tutored.

This painting is not just a simple portrait. The young man, Arnold, gazes at the viewer with a look of both innocence and curiosity. The backdrop holds an important part of the story — two nude men enjoy a river swim. All this takes place in a tranquil countryside.

But sadly, this masterpiece was kept hidden for years. Around a decade after its inception, signs of aging started to show — discoloration, varnish loss and an overall deteriorated look. The bathing men, once clear figures, were now almost erased.

However, 1985 brought relief for this painting. The forgotten portrait underwent a full restoration. And with that, “Arnold Comes of Age” finally got its due recognition. It’s not just paint on canvas but a rich narrative of friendship, admiration and strong affection.

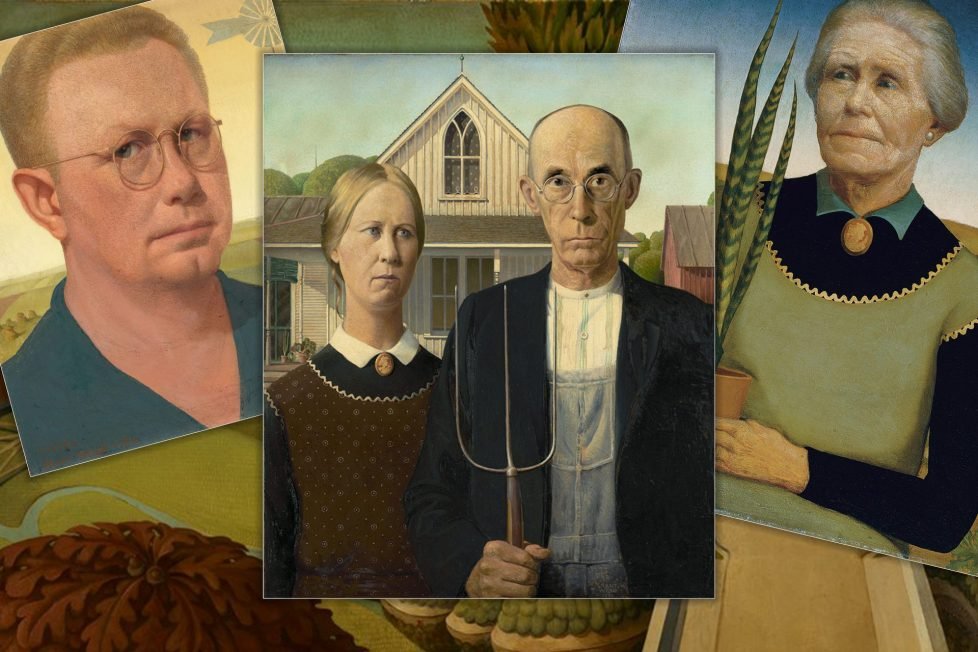

“American Gothic” is no ordinary painting. It is a tale of survival, grit and old-school charm. Painted during the Great Depression, it emerged as an emblem of undying American spirit.

In this piece, Grant Wood showcases a hearty farmer and his daughter (often mistakenly believed to be his wife). Outdated clothing marks them as figures from the past — a subtle nod to Wood’s family photos.

This painting sparked many debates and interpretations. One of which is that it’s an old-fashioned mourning portrait. Looking closely you’ll notice pulled curtains — a Victorian mourning custom. The woman wears black beneath her apron, casts a troubled gaze, and maybe fights back tears?

“American Gothic” is a testament to unyielding resolve, a look into a troubled past, and perhaps, an exploration of life and loss.

“Stone City, Iowa” was painted the same year as his famous “American Gothic” and tells a compelling tale. This isn’t just a beautifully composed view of Stone City but also a story of change. Wood perfectly captures the tranquil harmony of life with nature while subtly hinting at the scars of industrialization.

Stone City, positioned on the Wapsipinicon River, experienced both boom and bust. How? Well, its limestone quarries that brought prosperity eventually dried up due to the emergence of Portland cement. But in Wood’s painting, the land is reborn — thriving with crops and grazing animals. It’s as if Wood is suggesting that the aftermath of industrialization can lead back to simpler, purer roots.

Wood’s passion for Stone City didn’t stop at the canvas. He nourished the artistic spirit there, running a summer artist’s colony from 1932 to 1933. This little town inspired not just a single painting, but possibly an entire generation of artists.

Welcome to the visual conversation that is “The Appraisal”, a 1931 winner at the Iowa State Fair art competition. In the painting, two worlds collide. A city woman, decked out in a trendy style, meets a striped-cap wearing, woolen-jacket clad farm woman. What’s the story here? A close look shows the city woman clutching her beaded bag (full of money, we can guess!). In contrast, our farm lady holds her hen, destined for the city woman’s dinner plate. The true story of “The Appraisal” lies in their expressions. The tailored hat-wearing city woman reviews her future meal. The farm woman returns the gaze, unimpressed but not inferior in any way.

Despite the tacit snub from her fancy customer, the farm woman stands firm, signifying resilience. She’s proud of her ability to support herself and her family on the farm. Young plants in the backdrop foreshadow the coming spring, promising hope and rebirth. This painting speaks of contrast, resilience, and the unwavering dignity of a hard-working woman during the toughest of times.

Grant Wood’s “Victorian Survival” is an intriguing passageway between the past and the future. Painted in 1931, this artwork adds a twist to the painter’s familiar world, wrestling with technological transformation.

The painting showcases Wood’s great aunt, Matilda Peet. Dressed in black, she is an emblem of solemnity and tradition. Her rigid stature and stern garb make her a fortress against change. Then there’s the telephone. It may look old-fashioned to us, yet it is a surprising dash of modernity intruding on Matilda’s rigid world. Placed strategically, it nudges her off-center in the painting. It’s only a matter of time before it rings, stirring the calm waters of Matilda’s constant universe.

Through “Victorian Survival”, Wood cleverly stages a meeting of two worlds — one safe in its age-old ways, the other full of promise yet terrifying in its novelty. This striking blend signifies a profound dialogue between the traditional and the modern.

“The Birthplace of Herbert Hoover” is a 1931 work by Grant Wood. In this piece, the layout might feel oddly perfect — that’s Wood’s precision and love for harmony at play! The rural tranquility in this picture was tailored for then-President Hoover. A group of Iowa businessmen commissioned it, intending to present it to Hoover.

Smack in the center, behind the two-story house, is a white cabin. That’s Hoover’s true birthplace. Known for flaunting his humble roots during his presidential campaigns, this detail was aimed at pulling Hoover’s heartstrings.

But the plot thickens!

Hoover ultimately rejected the painting. Why? He felt the sizable house overshadowed his birth cabin. Yet like any good story, this one’s got a happy ending. Wood didn’t let the rejection dampen his spirits. He sold the painting through a dealer.

“Young Corn” is a 1931 Wood creation that paints a charming landscape, complete with a small hill speckled with fields to the left. Trees lined up to the right add a splash of whimsy, resembling sketches right out of a children’s book.

Another genius touch is Wood’s play with angles and perspective. The nearest field falls away down the slope, creating illusions of depth. A meandering path in the foreground passes a cozy home, probably a haven for the rural workers. In the low ground between hills, you can spot figures toiling away, their daily chores punctuating the drowsy tranquility. The mood is uplifting, thanks to the sun bathing the scene in bright light, only sparing the base of some trees.

The steep hills might raise eyebrows — are they too angled for corn? But that’s precisely Wood’s goal: manipulating reality to bid a more engaging, lively, and interesting visual treat! “Young Corn” beautifully blends rural charm and artistic imagination.

“Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” paints a picture of the famous American patriot, Paul Revere, during an iconic moment in American history — his midnight ride on the eve of April 18, 1775, to warn of the coming of British soldiers.

What makes this painting stand out is its unique perspective. It portrays Revere’s night ride through the brightly illuminated town of Lexington, Massachusetts, from a bird’s eye view. It offers a glimpse of how bustling the town might have looked that fateful night. The painting is not merely an illustration of historical facts, it was inspired by a renowned poem, “Paul Revere’s Ride” penned by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in 1860.

A fun fact about this great masterpiece lies in its details. Would you believe that Wood used a child’s hobby horse as a model for Revere’s horse? This little detail showcases the artist’s approach to his work. “Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” is more than just a painting. It is a blend of history, poetry, and artistic improvisation.

“Plaid Sweater” (1931) captures the youthful innocence of a young boy standing in a scenic and peaceful landscape. His fashion is a stand-out feature of the painting. He is snugly fitted into a bright red argyle sweater, tucked neatly into his pants. The vibrant red hue of his sweater pops against the calming fall backdrop, making him the center of attention.

In his hands are symbols of an all-American pastime: football. The way he holds a football and a helmet in his hands showcases a sense of childlike eagerness and enthusiasm for the game. Thus indicating Wood’s objective to portray wholesome, everyday American life.

The landscape setting adds a layer of depth to it. The holistic nature of this piece is an example of Wood’s genius. His usage of everyday items and settings to convey the mundane yet charming aspects of American life is phenomenal. “Plaid Sweater” is a harmonious blend of color, still life, and everyday Americana, all masterfully woven into one captivating artwork.

“Daughters of Revolution” was completed in 1932. It is an oil painting with a twist.

In this piece, the center of attention is the look of smug satisfaction on the faces of the portrayed ladies. A semblance of “Washington Crossing the Delaware” looms behind. Emanuel Leutze’s masterpiece sets a Revolutionary stage. So where is the twist? The women are the proud offspring of those Revolutionary heroes.

Completed in 1932, “Arbor Day” captures the peaceful essence of rural life. The scene unfurls a landscape dotted with farmhouses and barns. They are neatly tucked into rolling hills, as though playing hide-and-seek. Wood takes elements of the quiet American countryside and transforms them into visions of nursery-like innocence.

“Arbor Day” presents a familiar world, yet also dreamy. The depicted scene mirrors a child’s toy set — each object perfectly in its place, each property safe. It all seems as unblemished as an idealized childhood. Wood gives the viewer a peek into a time when life was simple and our surroundings were unthreatening. The landscape is a nostalgic nod to the times when security was not a privilege but a given. His painting becomes an escape into a safe haven — a world as serene, as it is secure, and inviting. Through “Arbor Day”, Wood assures us that art can be a soothing salve amidst the chaos of reality.

Grant Wood’s “Self-Portrait” (1932) is a striking piece. It truly shines a light on Wood’s intricate dance with European art styles. Think oil glazes on wood panels, an age-old technique used by Renaissance masters. He takes this up a notch by borrowing pointillism from Seurat’s playbook, a popular method that uses tiny dots of color to form pictures.

But Wood is nowhere near a European countryside or historic cityscape. No, he’s front and center amid the rolling plains of rural Iowa. Details in the painting pull you further into this narrative — a quintessential windmill turning in the breeze and corn shocks lined up like obedient soldiers.

These items aren’t just decor. They are powerful symbols of the Iowan countryside, tugged straight from Wood’s own life. Notice how he doesn’t pick a studio as his backdrop. Instead, he plants himself in the landscape he knows and loves. Throughout his artworks, you’ll find this subtle yet powerful affection towards his Midwest roots. It’s a love letter to his home, his art soaked in fond nostalgia for the world just outside his window.

As we’ve seen in the “Self-Portrait” section above, Wood is a midwest farm boy that let his roots inspire his art. Picture a youngster milking a cow. That’s the simple scene that Wood’s piece speaks to. But have you paused to ponder, why exactly a boy and cow? For Wood the answer lies in the near meditative rhythm of milking. A steady routine nurturing a bond between man and beast. That’s where Wood had his eureka moments, seeking solace in the rhythm of rural routines.

The art has an underlying allure — something inescapable and relatable. The boy could easily be any hardworking farmhand, the cow, any farm animal they nurture. It’s a potent picture of perseverance and patience. This connection, this pull, is what makes Wood’s works strike a chord. In “Boy Milking Cow”, the profound is wrapped up in the guise of the mundane. To fully tap into this treasure of a tale, one must look closer. Maybe, like Wood, we’ll all be inspired by the seemingly ordinary around us.

“Dinner for Threshers” is a painting that draws from Grant Wood’s childhood experiences living on an Iowa farm. Each year, there was a grand ritual — the harvest of the winter wheat or oat crop.

The local men garbed in jeans overalls, toiled in the fields. Women and children bustled in the kitchens, preparing a midday feast or “dinner”, as it was known in the Midwest. The painting gives us an intimate peek into a farmhouse, echoing a work of Renaissance art that depicted Christ’s Last Supper.

This comparison assigns an almost religious significance to the farmers’ meal. However, Wood steers clear of the bleak reality of the 1930s Great Depression in his piece. In fact, Iowa had one of the hardest hits, with a quarter of farms failing due to a brutal drought in the early part of the decade.

A study of this iconic painting, crafted with charcoal, pencil and chalk on brown paper, went up for sale in 2014. It fetched a staggering $1,565,000 at a Christie’s auction.

“Return from Bohemia” was created in 1935 while Wood was in Paris. But don’t let that fool you — he wasn’t swayed by Parisian sophistication. Instead he used Paris to trigger his nostalgia for good old Midwestern charm.

The figures in the painting? That’s his audience and his subject. Deceptively simple, but look closer. Notice their clothes — a blend of old and new. Suggestive, isn’t it? The juxtaposition here is evident and intentional.

Picture this — Wood in a barnyard, paintbrush in hand. That’s the image he depicted for his autobiography’s jacket illustration. The book was his way of putting his Midwestern roots under the lens, an homage to his formative years on a farm, and his rebound from his foray into Impressionism.

See how the character’s eyes are downcast? Wood poses a question with this depiction — what does his homecoming truly mean? The figures don’t appear to be looking at the masterpiece but at the earth beneath. It seems they’re lost in thought, just like Wood during his return from a bohemian lifestyle. As plain as they appear, they speak volumes about Wood’s personal journey and the public’s perception of him.

In this intriguing piece, Wood masterfully blends his personal evolution with a commentary on cultural shifts. A return from Bohemia wasn’t just his journey home, but also a return to his artistic roots.

“Death on the Ridge Road” portrays a disaster looming on a rural road. At its heart is a road, highlighted by parting clouds overhead that cast an eerie glow. The rest? Swallowed by darkness, giving an unsettling, trapped feel. It’s a suspenseful scene — stormy skies, two cars and a truck appear to be on a collision course. This ominous moment illuminates Grant Wood’s disdain for the intrusion of modernization into rural life.

Look closer. The slanted black car sprawls across the road, embodying reckless city culture. Its crash course? With the airborne truck, probably bearing farm goods, displaying the reckless speed of modernity that even rural folk must adopt to keep up. The other car, lingering in oblivion, reflects innocent bystanders thrust into this mess.

This bustling meander of city and rural life, according to Wood, is set to disastrously collide. Each element in this scene doesn’t merely represent a physical object, it gives voice to the fear of inevitable loss due to the unchecked march of technological progress. This isn’t just art, it’s a cry for a fading lifestyle and a testament to a time fading into dust.

“New Road” (1939) teems with vibrancy, capturing an idealized American countryside. The square canvas showcases rolling green fields partitioned by contrasting sand-colored roads. Wood’s use of light creates a warm, almost sunset like ambiance.

A road seems to tumble into a lush valley from a hill, dotted with wooden posts hosting a sign reading “SOLON 5 MI”. Fields are meticulously cross-hatched, rich in clay-orange strokes adding texture. A white farmhouse nestled amidst trees, a host of pom-pom shaped trees, a brick-red barn and a windmill present classic rural scenery.

Flecks of white throughout hint at farm animals and fence posts. The sky, a tapestry of short, soft strokes transitioning from tranquil blues to peach and pink hues, suggest a setting sun. Together, these elements fuse to create Wood’s quintessential representation of rural American life.

“Parson Weems’ Fable” (1939) channels the well-known tale of a young George Washington and his cherry tree. Grant Wood used this canvas to take America back in time. His intent was a sweet reminder of its democratic roots during a period of the 20th century when Europe was falling under the menacing cloud of fascism.

Weems, the fable’s author, is seen drawing back a curtain in the painting. He directs our eyes towards a small but sure-footed George. Adding a humorous twist, Wood gives the boy George an adult-sized head. This was modeled on Gilbert Stuart’s 18th century portrait of Washington. You may recognize this face from the one-dollar bill!

In the background, African Americans pick cherries. A quiet, somber reminder of Washington’s life, which despite his groundbreaking role at the helm of a young, independent nation, was stained by the fact that he owned slaves. With this poignant detail, Wood subtly underlines the contradictions of America’s past, ensuring viewers don’t forget the complexity of their history.

“Haying” introduces us to harvest time in 1939. The canvas follows rolling hills teeming with orderly haystacks, symbolizing hard work. An almost-hidden young tree and two striking red barns break the sea of hay. One barn has a lantern-shaped cupola, a detail typical of Wood’s meticulous style. A rustic weathervane tops the other.

A lone ceramic jug rests in the foreground, signaling a moment’s rest amidst a busy harvest. All these are backdropped by a light blue sky, creating an idyllic rural tableau. Wood’s painting, filled with vibrant colors and thoughtful details, tells a story of rural American productivity captured beautifully on canvas.

“January” (1940) is one of Wood’s last masterpieces. He tragically died from liver cancer soon after. The painting vividly encaptures nostalgic themes. Wood himself tied this artwork deeply to his early farm life in Iowa. The painting displays an interesting tranquility. Wood framed it as “a land of plenty” that remains serene under the cold. It doesn’t suffer but rests. In the quiet and dormant scene, a glimpse of life appears. Tiny rabbit tracks hint at a whisper of activity amidst the chill.

Wood’s artistry shines through his clever use of abstract design. Take a close look at the pattern of the snow-laden corn shocks. They artistically plunge into the painting’s depth. The geometric alignment displays a rhythmic beauty. It’s as if they stretch infinitely into the far distance.

Furthermore, the painting’s motif demonstrates his penchant for agricultural imagery, evoking feelings of warmth, comfort, and an underlying sadness. This piece beautifully signifies an end of an era and a journey into the unknown.

“Spring in Town” is like a time capsule of small-town America in 1941. It transports you straight to a typical backyard scene. Just imagine local gardeners, bending to sow potatoes and onions as the March sun lavishes warmth over their efforts.

Wood found deep inspiration in the works of 16th-century artists such as Jan Van Eyck. Their hard-edged, detailed realism influenced his style. Look closely and you’ll notice this in his distinctive undulated forms. In this perfected vision of the American heartland, industrious neighbors are depicted as they plant gardens, mow the lawn, fix roofs, and clean their homes.

But “Spring in Town” is not just a past-paced idyllic portrait. See those industrial smokestacks distantly sketched? They symbolize the dawning of inevitable change on the agrarian landscape. It’s a touch of nostalgia, a longing for a simpler time.

A piece of trivia: this artwork shares the honor of being one of Wood’s final two pieces. He was painting this side-by-side with “Spring in the Country” in 1941, marking a remarkable ending to his artistic journey.

“Spring in the Country” (1941) captures the charm of rural life. A woman and a boy in overalls plant seedlings, working in tidy furrows marked with twine. Nearby, a man leads two plowing horses towards them. A herd of cows grazes under a blue sky while fluffy clouds float by.

Wood’s expert blend of green, brown, and blue hues bring his childhood memories to life. He recreates a simple, peaceful world before his ultimate passing in 1942. Look closer, and you’ll see a heartfelt tribute to his own parents. “Spring in the Country” is a final, genuine glance into Wood’s inside world and the beauty of simpler times.

In the final stretch of his life, Grant Wood painted captivating depictions of rural America, creating a legacy that now extends far beyond “American Gothic”. His unblemished portrayal of country life, detailed brushwork, and warm hues invite us into his childhood memories.

One prevalent theme in his later works is candid simplicity. His characters are everyday folks, engaged in everyday tasks, in everyday settings. This sincere simplicity resonated deeply with viewers then and continues to do so today. Even in his last painting, “Spring in the Country”, he made sure to leave us with an enduring taste of his childhood tranquility.

Wood passed away in 1942, but his spirit lives on through his art. His paintings serve as a window to America’s peaceful past, reminders of the serene landscapes and humble people that once filled its canvas. As we step back from his works, we’re left with a profound sense of nostalgia, peppered with appreciation for the simple, beautiful things in life. Now that’s a legacy to remember!