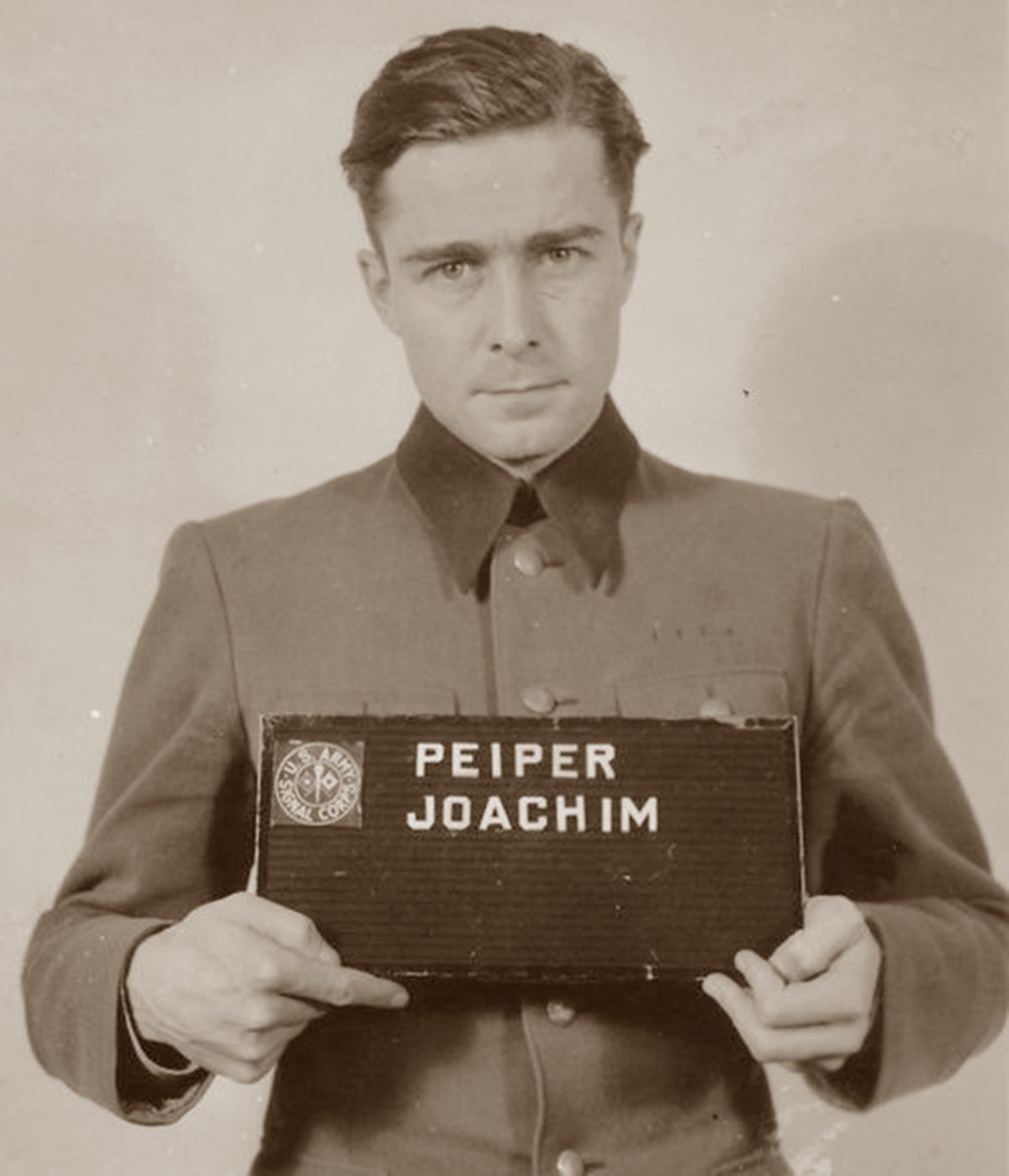

Joachim Peiper, His Military Career and the Malmedy Massacre

An in-depth look at Joachim Peiper's SS career and role in the Malmedy massacre during World War II.

An in-depth look at Joachim Peiper's SS career and role in the Malmedy massacre during World War II.

Table of Contents

ToggleJoachim Peiper was a highly notorious SS officer who served during the Second World War. He was convicted of war crimes committed by his troops at the “Malmedy Massacre” during the Battle of the Bulge German counter attack in December 1944. Until his violent death in 1976 (most likely at the hands of French anti-Nazis) he remained an unrepentant supporter of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime. In the decades after the Second World War he has become almost the definitive cliché of an aggressive, ruthless SS officer.

Peiper was born in January 1915, the third son of an officer who had served in the Imperial German Army and who brought his sons up to be strongly nationalistic. He joined the Hitler Youth in the early 1930s and, shortly afterwards, the SS, joining the Nazi party in 1938. He was good-looking, intelligent and proactive. He came to the attention of Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS and served for some time as Himmler’s personal adjutant. It was in this capacity, accompanying Himmler on official duties, that he gained a wider understanding of the extermination policies of the Third Reich directed against Jews and other social groups, including witnessing Jewish ghettos and the execution of Poles and insane asylum patients.

When Joachim Peiper got married, in 1939, Himmler was the guest of honour. By the time the war started, Peiper was fully encased in the ideology of Nazism and totally loyal to it – including a ruthless and callous approach to life if it got in the way of Nazi ideals or military missions.

His military career began with Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler SS (LAH), originally a regiment designed as Hitler’s personal bodyguard, but expanded during the war into a mechanised division and then an armoured division. From the start, Peiper performed well in combat. Peiper initially commanded a platoon in France and reportedly acting bravely and decisively, ending up as a company commander. He received the Iron Cross for capturing a French artillery battery. He then returned to serve again on Himmler’s personal staff.

The German army invaded Russia on 22 June 1941 as part of Operation Barbarossa. Peiper rejoined the LAH as part of the divisional staff in August and served with them in the south, in the Black Sea/Taganrog area. He took over command of the 11th company. In June 1942 the LAH left Russia for France in order to regroup and refit. The LAH were expanded and equipped to be a panzer grenadier division. Operating as a mobile unit with half tracks and trucks. Peiper was made a battalion commander in January 1943, commanding the 3rd battalion of the 2nd Panzer Grenadier Regiment.

The division was sent back to the eastern front in January 1943, where they soon engaged in bitter fighting in and around the city of Kharkov, which had changed hands several times. In a special mission, Peiper’s battalion was sent behind Soviet lines in order to rescue the 320th infantry division, which had been cut off during a rapid Soviet advance. The LAH, including Peiper and his battalion engaged in the wholesale destruction of Russian villages and the execution of many Russian civilians.

Over the summer, the division readied itself for the titanic battle of Kursk, which commenced on 5 July. But, when Sicily was invaded by the Allies on 9 July, the LAH was pulled out and sent to northern Italy, arriving there in August.

On 19th September, Peiper’s forces were at the village of Boves when twenty-three Italian civilians were shot dead and the village burned down. Peiper had been trying to secure the release of two of his soldiers captured by partisans. The actions of the German soldiers were brutal and went beyond self-defence and into gratuitous violence. But information about the controversial incident in the post-war period – which saw Peiper accused of war crimes – was contradictory and difficult to confirm. In 1968 an Italian court concluded that there was insufficient evidence to justify prosecution.

In October, the LAH reorganised again, as a panzer division. Peiper was made Lieutenant Colonel in January 1944 and given command of the 1st Panzer Regiment. At this point, health check ups showed he was suffering from combat exhaustion and made to take leave.

Returning to the regiment – then in Belgium – in April 1944, he set about a harsh regime of training for the new recruits to the LAH. He was a strict disciplinarian, reportedly executing four young soldiers for stealing chickens.

The division stayed in Belgium during the first months of fighting in Normandy after the 6th June D-Day landings – part of Hitler’s fear that Normandy was a feint. The LAH arrived in Normandy on 6 July and was instantly in action against the Americans. But there were more health problems – perhaps a natural feature of someone who has been in extensive combat operations over a period of years. Peiper contracted jaundice in late July and on 2 August was sent back to Germany for rest, not to rejoin the regiment until October.

Since the failed Allied airborne operation “Market Garden” in mid-September, Adolf Hitler had been pondering opportunities for a large-scale counter-attack on the western front. Using the best of the reserves and resources at his disposal he created two new armies – one of them a panzer army, stacked with SS formations – and readied them in and around the Ardennes forest, which, at this point in time, was thinly held by inexperienced American troops.

With his background – fanatical, highly decorated and ruthless – Peiper was a natural choice to be at the forefront of Hitler’s great Battle of the Bulge gamble. He had already been sounded out – planning staff had asked him how long it might take to drive an armoured force eighty kilometres at night. Pieper took a Panther tank and tried it himself before reporting back. His force – Kampfgruppe (battle group) Peiper – was charged with punching through the American lines and reaching bridges on the Meuse river more or less at all costs – even if it meant pushing German troops out of the way. The kampfgruppe was reinforced, including with the 501st heavy tank battalion equipped with Tiger I and Tiger II “King Tiger”. Failure could not be countenanced.

But the mission was a tough one. Even if American resistance was relatively weak initially, muddy dirt tracks, rugged forested and hilly terrain, winter conditions and the requirement to move thousands of troops and vehicles all at the same time were challenging enough. Fuel and ammunition was also limited – the advancing panzers were hoping to capture Allied supply dumps along the way. Fanaticism alone would probably not be sufficient.

The operation was scheduled for 16th December, but delays were apparent even from the start. The road network of the Ardennes was not designed for heavy armour – and the German tanks of 1944 were bigger and heavier than the panzers of 1940. Enormous traffic jams were caused by horse and truck columns of the non-mechanised forces in front of Peiper. Peiper’s own column stretched back twenty-five kilometres. He chafed in frustration. Some of his wheeled vehicles had to be towed. Although they captured an American fuel dump on 17 December, the timetable was falling apart and the pressure on Peiper to push forward was intense. Later that day, the kampfgruppe ambushed a retreating column of thirty American military vehicles, taking dozens of prisoners from the 258th Field Artillery Observation Battalion. It is highly likely that Peiper’s desperation to get his mission done (prisoners could not be brought along) and the routine brutality of SS operations after years in Russia greatly contributed to what happened next. The Americans were disarmed and made to wait in a snowy field. After a signal, machine guns opened up and most of the Americans were left dead or dying. Wounded prisoners were later shot in the head where they lay. Others at the back of the group managed to flee into a forest and brought news of the massacre back to the American commanders. At this time, in neighbouring villages, other Americans and Belgians were executed.

Peiper’s military situation worsened by the hour – the Ambleve valley was narrow and unsuited for heavy armour. Some of the bridges would not bear the weight of the King Tigers, greatly limiting his options. His armour moved back and forth, trying to find a viable route forwards. He was running out of food, fuel and ammunition, despite receiving a rare Luftwaffe aerial supply drop. When American troops cut him off in the rear, he was faced with the decision to abandon his vehicles and equipment and try to break out. Of a force of 3,000, only about 700 managed to get back to German lines.

Peiper was decorated again, despite his failure and was sent to the eastern front – by now, this meant Hungary. By the end of the war, in May 1945, the LAH was ordered to surrender to the Americans (rather than face almost certain execution at the hands of the Soviets). Peiper ignored this and set off for home on his own. He was arrested by the Americans later that month and charged with war crimes during the Battle of the Bulge – specifically in and around Malmedy (the actual site of the massacre was a crossroads at Baugnez).

Peiper and 73 former SS co-defendants protested innocence. Peiper argued that the Belgian civilians had been partisans. There were many irregularities in the court proceedings – many of the defendants had been beaten, intimidated and given mock trials – but the immediate post-war mood towards the SS was unsympathetic, to say the least.

Peiper was sentenced to death. In 1951 this was commuted to life imprisonment. In 1956 he was released on parole. Undercover networks of ex-Nazis found employment for him at Porsche for a time. But he chose to keep a low profile and moved to a remote part of eastern France – perhaps a curious choice for a convicted Nazi war criminal – where he worked as a freelance translator, under the pseudonym “Rainer Buschmann”. He was guarded about his SS past, but was not entirely anonymous – he even chose to speak to journalists on occasion. His identity leaked out. Following some derogatory comments about France, he began to receive threats and warnings from local Frenchmen who may have been resistance fighters during the war. On 14 July – Bastille Day – 1976, there was an armed stand-off between Peiper and a dozen Frenchmen. Details are unclear, but, after a shootout, Peiper’s house was burnt to the ground and Peiper’s blackened, shrivelled, corpse found inside. The coroner’s cause of death for the badly burned body was given as smoke inhalation.

Peiper’s luck had finally run out.